a strange knowing,

a strange language.

By Giles Tettey Nartey

![]()

Strange Notes, Giles Tettey Nartey, 2025

Valentin-Yves Mudimbe’s The Invention of Africa puts forward the assertion that the very idea of “Africa” emerged through Western categories and prejudicial modes of classification. These categories produced an image of the continent shaped for Western consumption and, crucially, through Western comprehension. Mudimbe traces a historical sequence: early explorers, followed by missionaries, and later anthropologists, each working from an external vantage. Their accounts reduced the complexity they encountered, translating unfamiliar worlds into narratives that aligned with a eurocentric epistemological framework. These narratives circulated as stories brought back to populations eager to hear of distant places. In the process, wisdoms, rituals, and cosmological orientations that exceeded Western philological traditions were compressed, distorted, or erased. The resulting construction offered a simplified and misleading answer to the question “What is Africa?”, one shaped by reduction, omission, and the demands of legibility within a Western gaze.

Strange Notes, Giles Tettey Nartey, 2025

Valentin-Yves Mudimbe’s The Invention of Africa puts forward the assertion that the very idea of “Africa” emerged through Western categories and prejudicial modes of classification. These categories produced an image of the continent shaped for Western consumption and, crucially, through Western comprehension. Mudimbe traces a historical sequence: early explorers, followed by missionaries, and later anthropologists, each working from an external vantage. Their accounts reduced the complexity they encountered, translating unfamiliar worlds into narratives that aligned with a eurocentric epistemological framework. These narratives circulated as stories brought back to populations eager to hear of distant places. In the process, wisdoms, rituals, and cosmological orientations that exceeded Western philological traditions were compressed, distorted, or erased. The resulting construction offered a simplified and misleading answer to the question “What is Africa?”, one shaped by reduction, omission, and the demands of legibility within a Western gaze.

Mudimbe anchors this critique in the concept he names African Gnosis. The term designates indigenous systems of knowledge that operate beyond, and often against, the classificatory grids of Western epistemology. Drawing on the Greek gnosis, which means a form of knowing distinct from empirical or purely intellectual, African gnosis names a mode of understanding that is intuitive, embodied, and experiential.

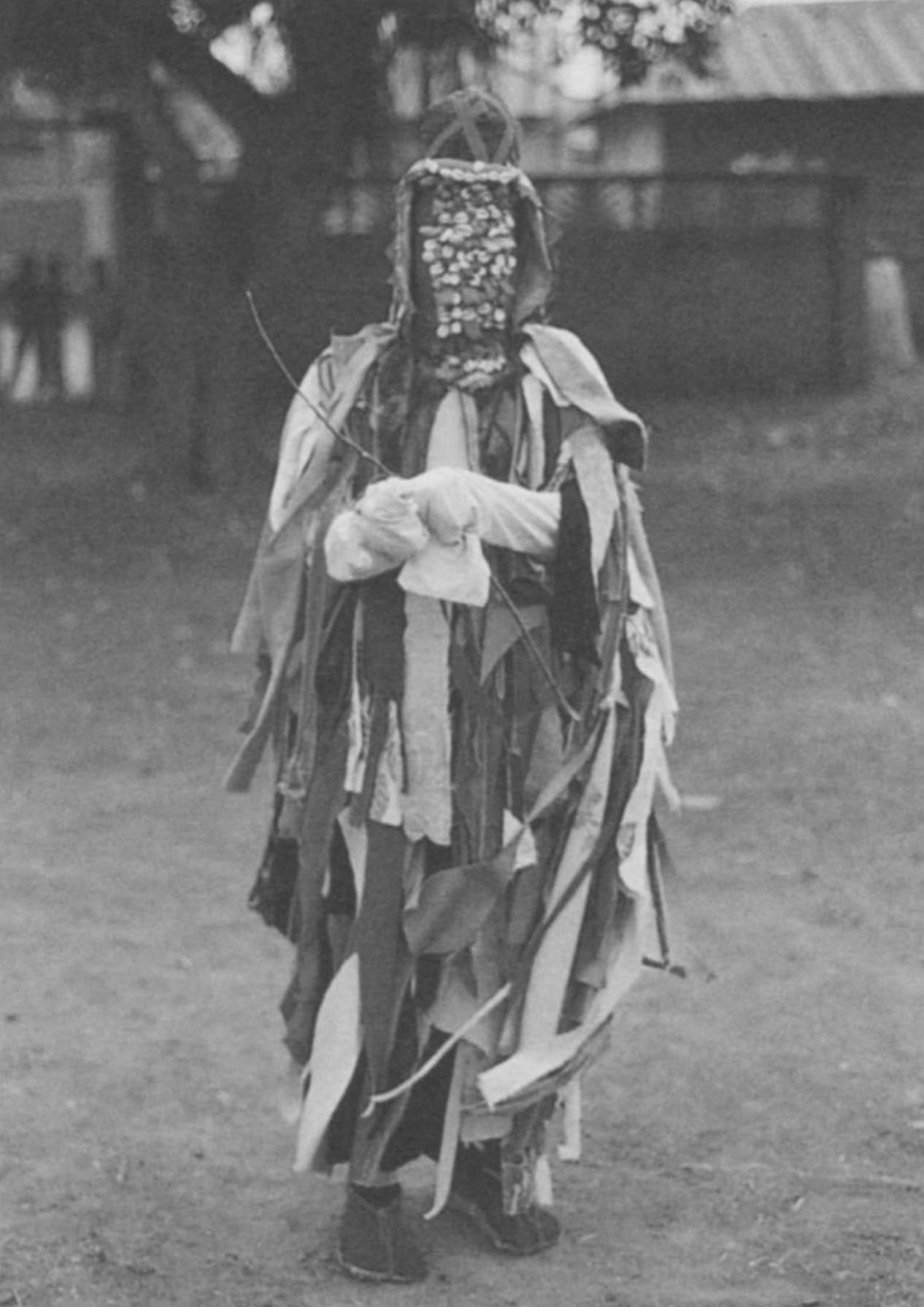

Devotee of Hu, God of Ocean in Cana, Benin, Suzanne Preston Blier

It resides in ritual, orature, and artefact; it moves through proverbs, gestures, stories, divination, and craft; and it remains inseparable from the practices and ecologies that sustain life. Mudimbe uses the term to mark a coherent and African-centred system of ordering knowledge. It names intellectual traditions that predated missionary and anthropological incursions and continued to exist alongside colonial rule, even as they were marginalised, misread, or dismissed as primitive.

Because these epistemic formations did not align with Eurocentric criteria for what counted as knowledge, colonial administrations reorganised societies through European modes of reasoning, classification, and institutional structure. This imposed reconfiguration produced enduring states of epistemic misalignment: people compelled to operate within external frameworks that diverged from the indigenous logics through which their societies had evolved. The result was a condition of limbo, suspended between epistemic disfigurement and a sustained amnesia that obscured older modes of knowing.

To ‘know’ something is often understood as the act of rendering it transparent, explaining, classifying, and placing it within a universal system of intelligibility. This demand for transparency aligns with colonial logics that translate difference into categories so it can be possessed, governed, or assimilated. States of unknowing or opacity are forcefully dismissed or violently made clear. Édouard Glissant’s writing on opacity is central to understanding this dynamic. He observes that “Western thought has imposed transparency and reduction as measures of truth. To know has too often meant to dominate, to order, to appropriate.” Glissant argues that peoples and cultures hold an inherent right to opacity. They do not need to be fully understood according to external terms in order to be valued or engaged. For Glissant opacity maintains the integrity of difference without the compulsion toward reduction. An African gnosis operates within this field of opacity, an embodied and intuitive mode of knowing that exceeds empirical comprehension and renders the question “What is Africa?” a hopelessly naïve and impossible question. An African gnosis presents a strange knowing and a strange language that moves beyond Western sensibilities.

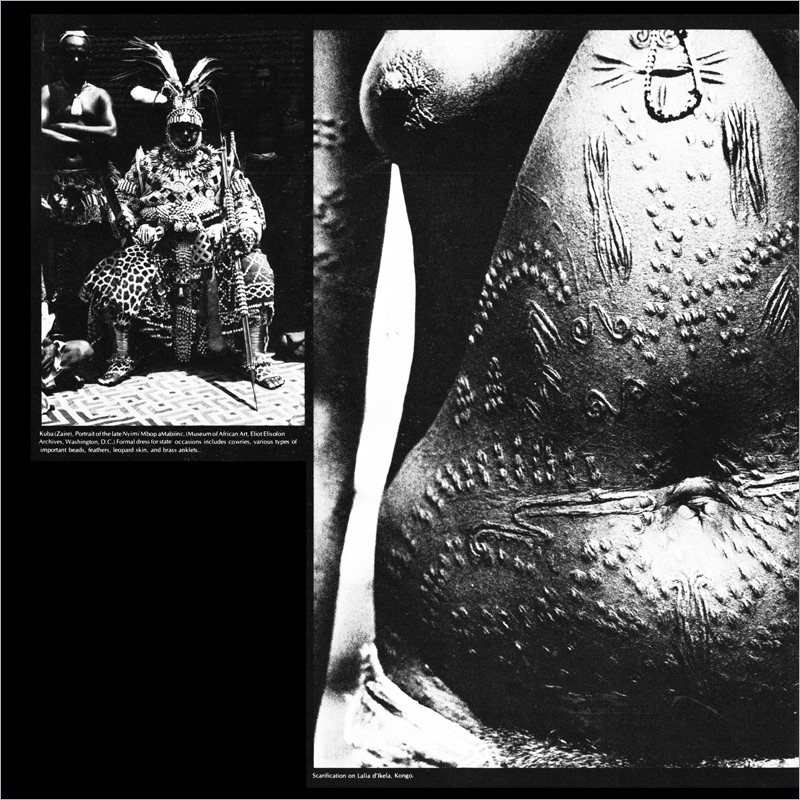

Accumulation: Power and Display in African Sculpture, ArtForum. 1975.

The phrase a ‘Strange Language’, framed through Mudimbe’s articulation of African gnosis, offers a conceptual grounding for my work and for my methodology as an architect- artist-researcher. My practice, across material, filmic, and spatial manifestations emerges from an ongoing preoccupation with ‘language’ and what it means to communicate through material creations. The work treats design as a linguistic act: a means of telling stories, revealing structures of value, and exposing the hierarchies that organise everyday life. Through this linguistic act design also becomes a conduit through which emotion can be transferred and felt, sensed or interpreted by those who encounter the work. The idea of a language is central to how I make and what I make. As a result of this interest what has concerned me and by extension my practice is what occurs when the language of a made-thing sits outside registers of familiarity, what emerges as a result of this unfamiliarity and what such unfamiliarity reveals about the assumptions through which we apprehend the world.

![]()

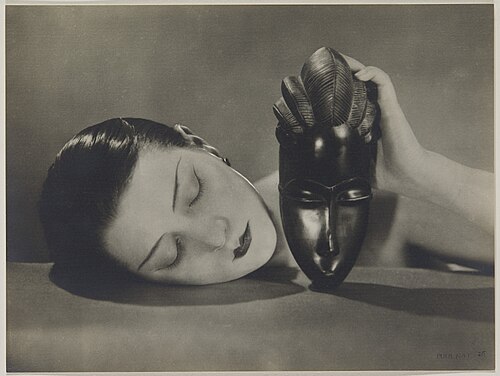

Noire et Blanche, Man Ray 1926

Strangeness surfaces in that moment of encounter, when the subject meets an object that speaks a different language. In that moment of attempted comprehension, perception reaches outward and meets a presence that withholds full legibility. This strangeness initiates an exchange, yet the exchange should not require clarification. It may remain opaque, allowing the encounter to unfold without the obligation of explanation. A friend and collaborator, Jonah Luswata, an architect and artist from African heritage, articulated the significance of this disruption in a conversation we had about the role of my practice as a whole—but specifically about SERWAA, a 6 legged reimagination of a traditional Lobi chair, SERWAA’s need to disturb and distort as a means of establishing a language in opposition to the contemporary Western design canon. Jonah said:

![]()

SERWAA, Giles Tettey Nartey, 2024

This surrealness has deep precedent in West African sculptural traditions, where deliberate distortion of the human figure or everyday objects expresses local and regional beliefs. These design practices use distortion as a mode of storytelling, spiritual invocation, and social commentary. In contrast to European traditions that have historically prioritised precision, realism, and accurate representation of the observable world, African craft and visual culture often employ asymmetry, elongation, fragmentation, and abstraction. This intentional and embodied strangeness offers insight into cultural worldviews, folk philosophical understandings, and symbolic meanings embedded within materials and forms. Distorted forms operate as tools for interpreting the values, priorities, and metaphysical orientations of particular communities. This logic extends to the body itself, where additions, adjustments, and transformations such as scarification or the elongation of the neck function as cultural expressions that reflect social ideals, identities, and cosmological orientations.

![]()

Strange Notes, Giles Tettey Nartey, 2025

The title draws from Christina Sharpe’s Ordinary Notes, which positions the note as a form of Black thought, a vessel for memory, and a mode through which the everyday becomes a site of Black knowledge-making. Sharpe shows how notes hold what cannot be fully systematised: they carry fragments, impressions, refusals, and intensities that resist the coherence demanded by dominant epistemologies. In my conception, the note is both sound and thought. It is a form of thinking that does not rely on linearity or transparency. To invoke the note is to invoke a way of attending to the world that values resonance over clarity, texture over definition.

![]()

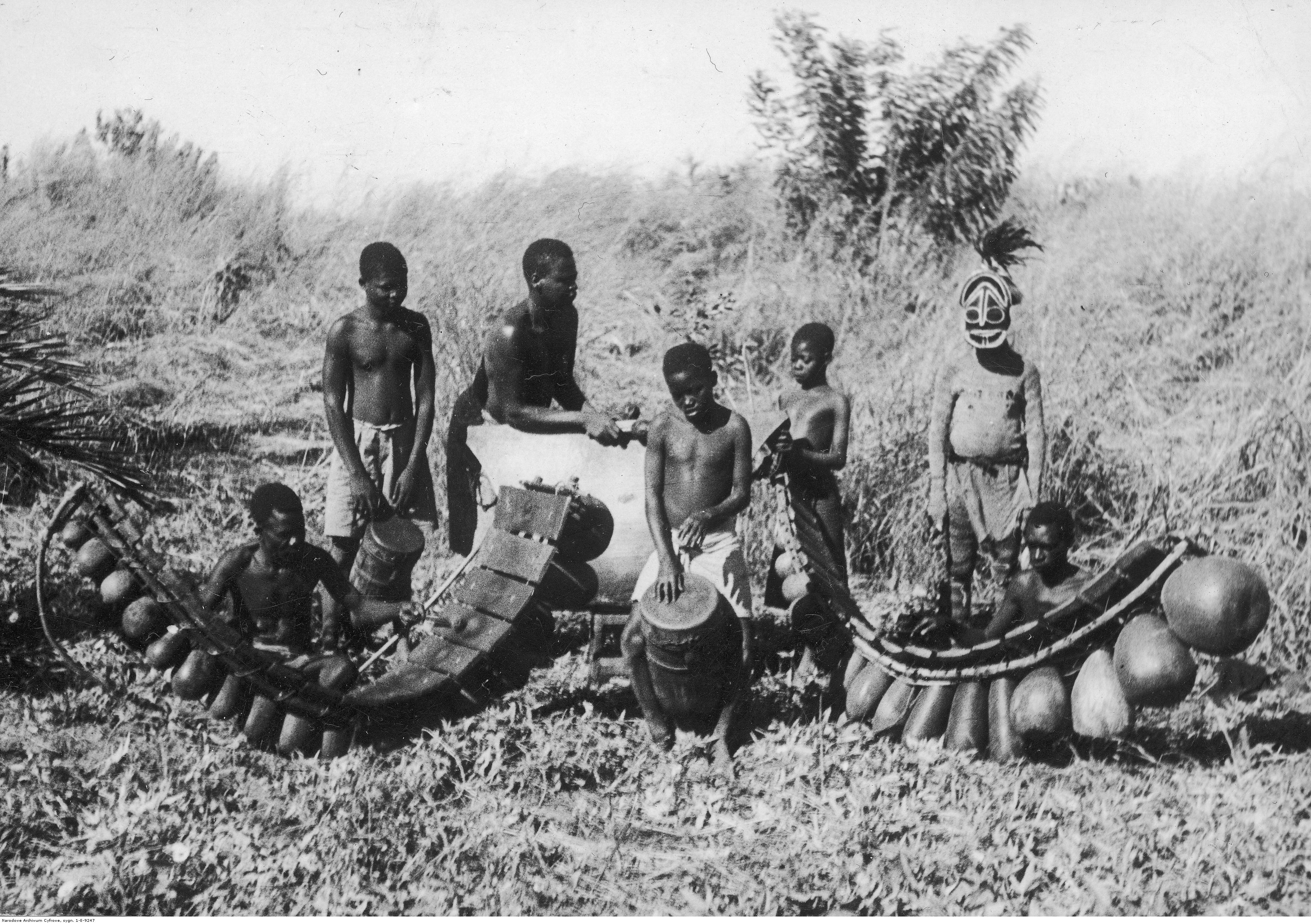

A tribal orchestra on the Lulua River, Congo, Kazimierz Nowak, 1935

The work proposes that strange notes are not manufactured but found. They emerge in the moment when material, body, and space align in ways that cannot be predicted or fully controlled. To register the strange is to listen differently. It requires an openness to frequencies that fall outside standard harmonics, to resonances that signal unfamiliar relations between matter and meaning. Strange notes mirror the larger epistemological claims of African gnosis and Glissantian opacity: knowledge does not need to be transparent to be present. It can be felt, sensed, and carried in sound, form, and relation. By drawing on Sharpe’s reflections, the work positions strangeness as a legitimate mode of encountering the world. It frames the strange not as a deviation from knowledge but as a knowledge practice in itself. To register the strange is to recognise that understanding may arise through intuition and resonance rather than through understanding. It invites us into a different kind of listening.

![]()

Accumulation: Power and Display in African Sculpture, ArtForum. 1975.

![]()

The phrase a ‘Strange Language’, framed through Mudimbe’s articulation of African gnosis, offers a conceptual grounding for my work and for my methodology as an architect- artist-researcher. My practice, across material, filmic, and spatial manifestations emerges from an ongoing preoccupation with ‘language’ and what it means to communicate through material creations. The work treats design as a linguistic act: a means of telling stories, revealing structures of value, and exposing the hierarchies that organise everyday life. Through this linguistic act design also becomes a conduit through which emotion can be transferred and felt, sensed or interpreted by those who encounter the work. The idea of a language is central to how I make and what I make. As a result of this interest what has concerned me and by extension my practice is what occurs when the language of a made-thing sits outside registers of familiarity, what emerges as a result of this unfamiliarity and what such unfamiliarity reveals about the assumptions through which we apprehend the world.

Strangeness arises at the edge of familiarity, when a form, gesture, or material vocabulary appears outside one’s frame of reference and unsettles habitual ways of reading the world. It introduces a different point of orientation. The perceived strangeness attributed to Africa and its material culture within art and design has long been constructed through an external gaze, particularly a Western gaze that encountered African objects from a position of unfamiliarity. Strangeness is not inherent to the objects themselves. It emerges through perceptual dissonance, in which Western aesthetic sensibilities struggle to apprehend forms rooted in different cultural logics. Masks, stools, anthropomorphic figures, and zoomorphic forms sat outside Western legibility and were classified as strange or alien. Even as these objects were decontextualised and removed from the worlds that generated them to satisfy European appetites for African curiosities, certain materials such as bone, raffia, pigments, or traces of blood were considered too unsettling and were removed and discarded in passage to European collections. They were made un-strange whenever their material assemblages proved disconcerting for a European eye. This management of strangeness is inseparable from processes of othering, in which African objects and bodies were designated as curiosities or as other, reinforcing a binary through which the European self-defined itself against a constructed alterity. As Stuart Hall argues in the chapter The Spectacle of the ‘Other’, dominant cultures stabilise their authority by producing such binaries, depicting the other as foreign, deviant, or enigmatic, and in doing so, naturalising hierarchies of power.

Noire et Blanche, Man Ray 1926

Strangeness surfaces in that moment of encounter, when the subject meets an object that speaks a different language. In that moment of attempted comprehension, perception reaches outward and meets a presence that withholds full legibility. This strangeness initiates an exchange, yet the exchange should not require clarification. It may remain opaque, allowing the encounter to unfold without the obligation of explanation. A friend and collaborator, Jonah Luswata, an architect and artist from African heritage, articulated the significance of this disruption in a conversation we had about the role of my practice as a whole—but specifically about SERWAA, a 6 legged reimagination of a traditional Lobi chair, SERWAA’s need to disturb and distort as a means of establishing a language in opposition to the contemporary Western design canon. Jonah said:

“I think the more your language is un-understandable the better. It should be strange and perverse and different—and markedly so. In that, it acts as a little violence. Small acts of violence—they are reneging on the canon of received formalities. I think a six-legged stool is better than a four.”

A six-legged object defies the logic of nature and familiarity. No mammal moves on six legs. The six-legged belongs to the insect world, the alien, the otherworldly. The six-legged stool is therefore inherently strange, an object positioned outside the natural order. It disrupts expectation and creates tension between balance and excess, structure and absurdity. The form proposes an act of distortion in which something has been added, extended, or deformed beyond perceived necessity. It introduces unease, a liminal presence in which the practical becomes uncanny and the familiar carries an undercurrent of dissonance. This proposition, that strangeness and distortion can operate as tools of critique, is central to my work and central to SERWAA: a deliberate manipulation of form to invoke a certain surrealness.

SERWAA, Giles Tettey Nartey, 2024

This surrealness has deep precedent in West African sculptural traditions, where deliberate distortion of the human figure or everyday objects expresses local and regional beliefs. These design practices use distortion as a mode of storytelling, spiritual invocation, and social commentary. In contrast to European traditions that have historically prioritised precision, realism, and accurate representation of the observable world, African craft and visual culture often employ asymmetry, elongation, fragmentation, and abstraction. This intentional and embodied strangeness offers insight into cultural worldviews, folk philosophical understandings, and symbolic meanings embedded within materials and forms. Distorted forms operate as tools for interpreting the values, priorities, and metaphysical orientations of particular communities. This logic extends to the body itself, where additions, adjustments, and transformations such as scarification or the elongation of the neck function as cultural expressions that reflect social ideals, identities, and cosmological orientations.

It could be said Western design conventions privilege rationality, clarity, and legibility. Form is expected to follow function, and objects are expected to be useful and immediately intelligible. A six-legged stool violates this order. It introduces an opacity. The six-legged form exists as a deliberate rejection of the idea that African design must conform to a Western canon. It asserts a different design language, one that embraces ambiguity. The sixth leg is not concerned with stability; it is concerned with presence.

So how do we register the strange? A recent work Strange Notes takes shape through this sensibility. The work is a contemporary reimagination of a west African balafon, composed of steel bars suspended over ceramic vessels held up by oak legs. Each component is tuned not through scientific calibration but through relation. Bar to vessel, hand to material, room to listener. The instrument is held together not by precision but by attunement. The work insists that very specific state where sound becomes music arises from encounter rather than from fixed measures. What is heard is contingent on proximity, weight, vibration, and the embodied gesture of the person who strikes the bar. In this way, Strange Notes becomes a study in relational acoustics, where strangeness appears as tonal deviation, as the excess or remainder produced when things come into contact.

Strange Notes, Giles Tettey Nartey, 2025

The title draws from Christina Sharpe’s Ordinary Notes, which positions the note as a form of Black thought, a vessel for memory, and a mode through which the everyday becomes a site of Black knowledge-making. Sharpe shows how notes hold what cannot be fully systematised: they carry fragments, impressions, refusals, and intensities that resist the coherence demanded by dominant epistemologies. In my conception, the note is both sound and thought. It is a form of thinking that does not rely on linearity or transparency. To invoke the note is to invoke a way of attending to the world that values resonance over clarity, texture over definition.

Within this project, strangeness becomes a register in its own right. It is a mode in which calibration is not empirical or absolute but felt. Strangeness is sensed rather than measured, received rather than decoded. It emerges when something sits outside familiar coordinates, when an encounter resists easy legibility. The strange unsettles the canon. This disruption is not an error but a mode of knowledge. It marks the moment where perception loosens, where the boundaries of comprehension give way to forms of sensing that exceed the empirical.

A tribal orchestra on the Lulua River, Congo, Kazimierz Nowak, 1935

The work proposes that strange notes are not manufactured but found. They emerge in the moment when material, body, and space align in ways that cannot be predicted or fully controlled. To register the strange is to listen differently. It requires an openness to frequencies that fall outside standard harmonics, to resonances that signal unfamiliar relations between matter and meaning. Strange notes mirror the larger epistemological claims of African gnosis and Glissantian opacity: knowledge does not need to be transparent to be present. It can be felt, sensed, and carried in sound, form, and relation. By drawing on Sharpe’s reflections, the work positions strangeness as a legitimate mode of encountering the world. It frames the strange not as a deviation from knowledge but as a knowledge practice in itself. To register the strange is to recognise that understanding may arise through intuition and resonance rather than through understanding. It invites us into a different kind of listening.

Strange notes lead us toward the broader question of how strangeness is held, materialised, and transmitted, whether through objects, gestures, or inscriptions. On 4 February 2025, during a conversation between the late Cameroonian Swiss curator Koyo Kouoh and artist Kendell Geers, Koyo reflected on the foundations of artistic practice as inseparable from the foundations of humanity. She proposed that humans orient themselves in the world through two enduring capacities: the making of objects and the making of scriptures. “We are made of objects and scriptures,” she said. “From ancient times, as we were becoming sapiens, we have made tools and objects. And our capacity to imagine and conceptualise writing and language will never change. We will always make objects and scriptures, and this is what I think makes us human.” These capacities shape how thought takes form. The making of objects reflects our ability to produce tools, artefacts, and material structures that carry utilitarian, symbolic, and aesthetic significance. The creation of scriptures describes our capacity for abstraction through language, writing, and notation. Objects function as material extensions of thought, while scripture codifies thought through symbolic systems. Together, they allow us to narrate the past, inhabit the present, and imagine the future.

Accumulation: Power and Display in African Sculpture, ArtForum. 1975.

The relation between these capacities becomes even more legible when read through the conjunction of poesis and the earlier discussion of gnosis. Whereas Koyo identifies the forms through which thought is externalised, poesis and gnosis describe the processes through which those forms come into being and acquire meaning. Poesis names the act of bringing something into existence, the world-forming labour of making. Gnosis names an embodied, intuitive mode of knowing that arises through practice, relation, and experience. Together, they unsettle inherited divisions between theory and practice, language and material, intellect and embodied action. They suggest that making can be a site of revelation, and that knowledge need not be transparent or empirical to hold value. They name the movement from the immaterial into the material, from sensing into form. They describe a mode of making in which knowledge is generated, held, and communicated without needing to be fully grasped. A strange language grounded in a strange knowing.

Strange Notes, Giles Tettey Nartey, 2025

1

V.Y. Mudimbe, The Invention of Africa: Gnosis, Philosophy, and the Order of Knowledge, African Systems of Thought (Indiana University Press, 1988)

2

V. Y. Mudimbe, ‘African Gnosis Philosophy and the Order of Knowledge: An Introduction’, African Studies Review 28, no. 2/3 (1985): 149–233

3

Édouard Glissant and Betsy Wing, Poetics of Relation (University of Michigan Press, 1997).

4

Julia Kelly, ‘The Ethnographic Turn’, in A Companion to Dada and Surrealism (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2016).

5

S. Hall and O. University, Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, COMM1107: (SAGE Publications, 1997).

6

S.P. Blier, African Vodun: Art, Psychology, and Power (University of Chicago Press, 1995).

7

C. Sharpe, Ordinary Notes (Daunt Books, 2023).

V.Y. Mudimbe, The Invention of Africa: Gnosis, Philosophy, and the Order of Knowledge, African Systems of Thought (Indiana University Press, 1988)

2

V. Y. Mudimbe, ‘African Gnosis Philosophy and the Order of Knowledge: An Introduction’, African Studies Review 28, no. 2/3 (1985): 149–233

3

Édouard Glissant and Betsy Wing, Poetics of Relation (University of Michigan Press, 1997).

4

Julia Kelly, ‘The Ethnographic Turn’, in A Companion to Dada and Surrealism (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2016).

5

S. Hall and O. University, Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, COMM1107: (SAGE Publications, 1997).

6

S.P. Blier, African Vodun: Art, Psychology, and Power (University of Chicago Press, 1995).

7

C. Sharpe, Ordinary Notes (Daunt Books, 2023).

Credits:

Images courtesy of Giles Tettey Nartey

Download PDF:

Get this article in print

21 January 2026

Share: Email, Instagram, WhatsApp