Doing the most with the least

In conversation with Charles O. Job

By Angel Harvey-Ideozu

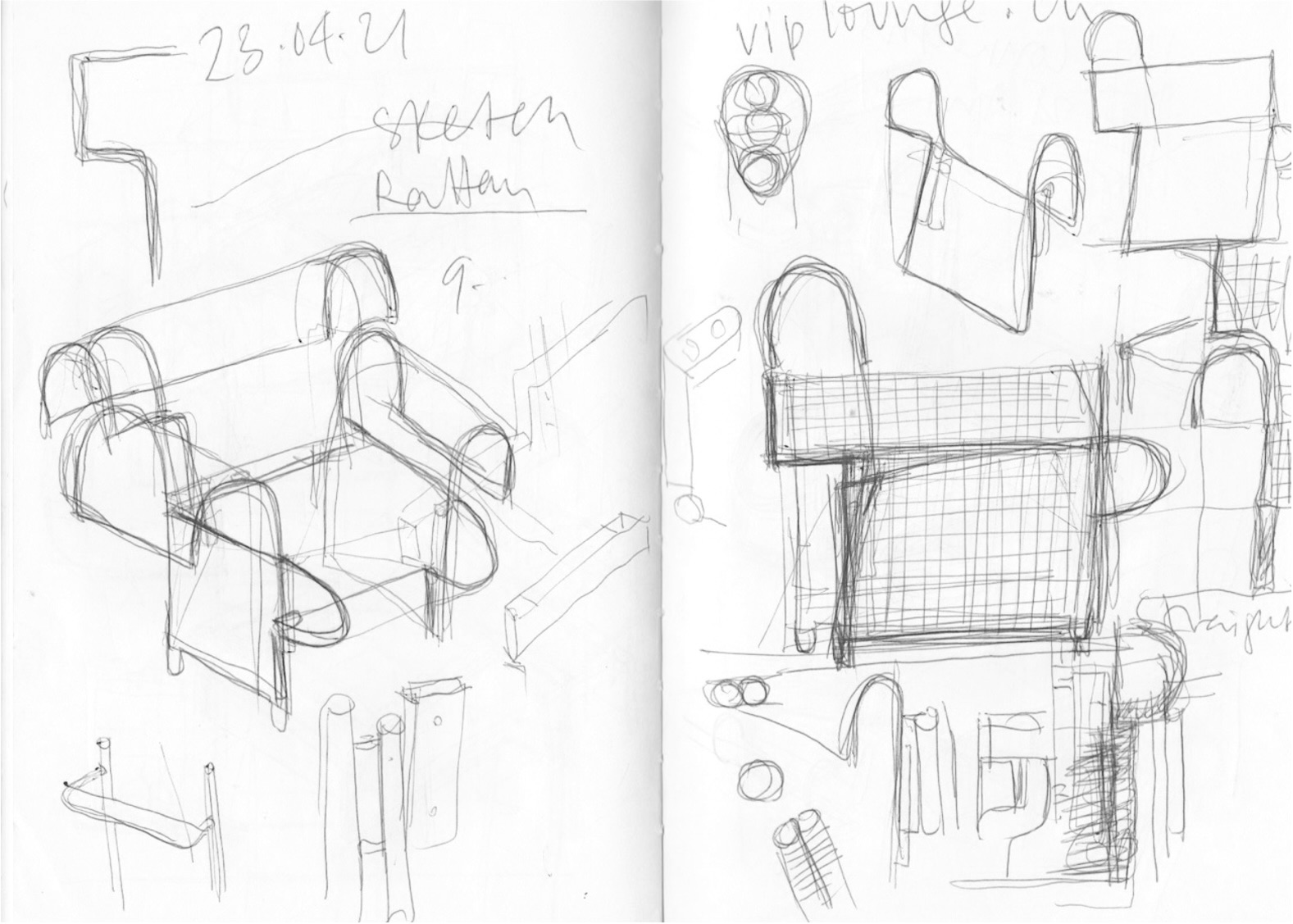

The story is known by now and needs minimal recap. As a child, Charles O. Job would fashion toys out of found materials, crafting curious playthings out of both need and want, in a practice he refers to as being not financially poor, but, instead, idea rich. For Okra’s first issue, I sat on a call with the Nigerian-born, Switzerland-based architect-cum-designer to reflect on this sustaining approach to design that takes the simple and everyday and turns it — through slights of hand performed in wood, metal, and colour — into beacons of great and simple design. From his flatpackable SKETCH plywood armchair which sits in the permanent collection of both the Vitra Design Museum and the Denver Art Museum, to his sketchbook drafts, we discussed accessibility as a guiding principle, and the complications in perception that come with creating works like he does as an African designer in an international landscape. There, he spins another beautiful reframe on how working with the minimum in fact makes him maximalist.

Angel Harvey-Ideozu:

So you used to make toys from found materials when you were a child growing up in Nigeria. What kind of toys were you making?

Charles O. Job:

We used to make watches with just a piece of glass and a bracelet. We also used to make these cars you pull around with you, and push empty wheels around the street with sticks. Silly things like that. But they were things that worked for us as children. We didn’t actually buy toys. We’d go out, look for the raw materials and put it together. You make what you need.

AHI:

Was there an element of escapism in that?

COJ:

Good question. Viewed from a distance, it does seem a little escapist. But the hard reality is less romantic. Girls plaited each other’s hair, grandpas farmed, grandmas cooked, and little children made playthings. It was part and parcel of the fabric of rural life in those days.

AHI:

Have you ever looked at any of your professional designs and thought, “I made a version of this when I was a child.”

COJ:

I think almost everything I do, to a certain extent, is a version of what I used to do as a child. Not because of what they look like, but because of the process behind them. You go out and you try and find something that you can actually work with. I have my sketchbook with me all the time, so when I see something it triggers something else. I’m always thinking, “What can I do with that?” I’m always referencing and turning my head and looking at something and getting inspired by just everyday things. Everything I do links back to that.

AHI:

How did you find that form for the SKETCH chair? A single form that repeats to make the back of a chair, the seat, and both arms-slash-legs. How did you arrive there?

COJ:

Well, I’ll show you where the shape comes from. Can you see this? This is a very traditional chair. I took that chair’s arm — that funny arm — and started playing with it. I thought, well if I want to make it cheaper, I could actually use this shape for each part of the chair. It probably took me about three or four weeks to come to that. When I got it, I thought, “That’s it!” So it came from a very traditional chair I’ve had for about 20 years, and then I translated it into something very simple, like a child would do. It’s not rocket science.

AHI:

Something you’ve had for 20 years finally rears its head and the lightbulb goes off.

COJ:

The thing about being a designer is that you’re surrounded by stuff. If you look hard enough, everything is actually around you. You just have to learn to look, take it all in, and let yourself be inspired.

AHI:

When did you really gain a drawing practice?

COJ:

The thing about drawing with the hand is that it’s there. You have a sketchbook and you can just open it wherever you want and do whatever. My sketchbook is always there. It’s accessible. I love it.

AHI:

You’ve spoken about how the energy from the act of making gets embedded into the object made, saying it “evokes a desire to possess and cherish the object.” Can you speak to me about the object, sort of as a general notion.

COJ:

When I say object, I actually mean things you can use: everyday things. I love objects that have a strong presence: where they’re there and can hold their own. So when I design products, I’m conscious of the fact that I want them to be in a house, in a setting, but also that they have to have a character of their own, because of their shape or their colour. They have to be able to stand on their own two feet. So for me, all the products I design, they’re not showing off, they’re trying to fit in but still be themselves and have their own character. They’re very characterful. They have a certain presence but they’re not shouting. They’re not loud, but they’re very proud. That’s how I see them. There’s a certain pride in being a chair, or being a CD or umbrella stand. And that fascinates me. Things that want to be something.

AHI:

Have you noticed for yourself, your tendency to animate these things.

COJ:

I’m conscious of the fact that when you put energy and resources into making something, it has to be something that somebody wants to keep forever and cherish. And I’m convinced that you can only cherish them if they fulfill some kind of a need and are beautiful. So not just a cup, but a beautiful cup. That’s how I see it. Something that speaks to somebody that makes them want to keep them forever and ever and ever.

AHI:

How do you consider your bilateral identities as African and European, architect and designer?

COJ:

I mean, most Italian architects were designers. Architects actually have an eye for furniture and design, so that to me isn’t such a big deal. But the African/European thing is quite interesting, because I believe a lot of cultures have this intrinsic culture of making stuff. It’s not an industrial culture but a pre-industrial one. My wife is Swiss and she comes from a village where people still use their hands to make stuff. So this culture of making isn’t particularly African or European, but to do with a context where people still connect with the earth, live a lot simpler, and make intuitively. So I think the parallels are there, but it’s not African or European. It’s a human thing. Making things is very human. It’s just what we make of it that’s different.

AHI:

Is that sentiment received when you show work?

COJ:

The funny thing is, people always say [my work is] minimalist. And I say, “Well, whatever that means.” To them the work is European, but the question is, where in Europe? Because it could be Swedish, Norwegian, or Scandinavian. And it could be, but it isn’t. Most African furniture is actually quite simple. If you take away the decoration, it’s all very very pared down. It’s not particularly African or European. [My objects] are simple because the person who made them thinks simply. The challenge for me is making something with very little resources. And if that’s perceived as being very minimalistic in whichever context, sure. I’m not a minimalist, but I mean… I think it’s actually very maximalist because I take it and do the most out of it with little resources.

AHI:

Oh, that’s a good line.

COJ:

I believe it! I’m maximising the potential.

AHI:

Between the Vis-a-Vis and B&B benches and the Duo chair, it seems like you’re sort of out to create a less hostile world, thinking about conviviality and sustainable practices. What’s the vision of the world according to Charles O. Job?

COJ:

I’m interested in seeing what design can do. We can’t solve all the problems, but aside from just making pretty objects, maybe we can actually do things and develop ideas that integrate, unite, reunite, and celebrate humanity.

Credits:

All images courtesy of Charles O. Job

Download PDF:

Get this article in print

21 January 2026

Share: Email, Instagram, WhatsApp