Form and Meaning: Objects, Ritual Choreographies, and the Soul

How Spiritual Objects Take On Meaning and Leave an ImpressionBy Angel Harvey-Ideozu

![]()

Across Black indigenous and diasporic populations, traditional and cosmologically adapted spiritual practices — though they tend to be blanketed under the illusory, not-quite-descript and vague term of ‘Black Mysticism’ — are defined and practiced in distinctly separate ways around the world, according to the specific social, cultural and geographical contexts from which they root.

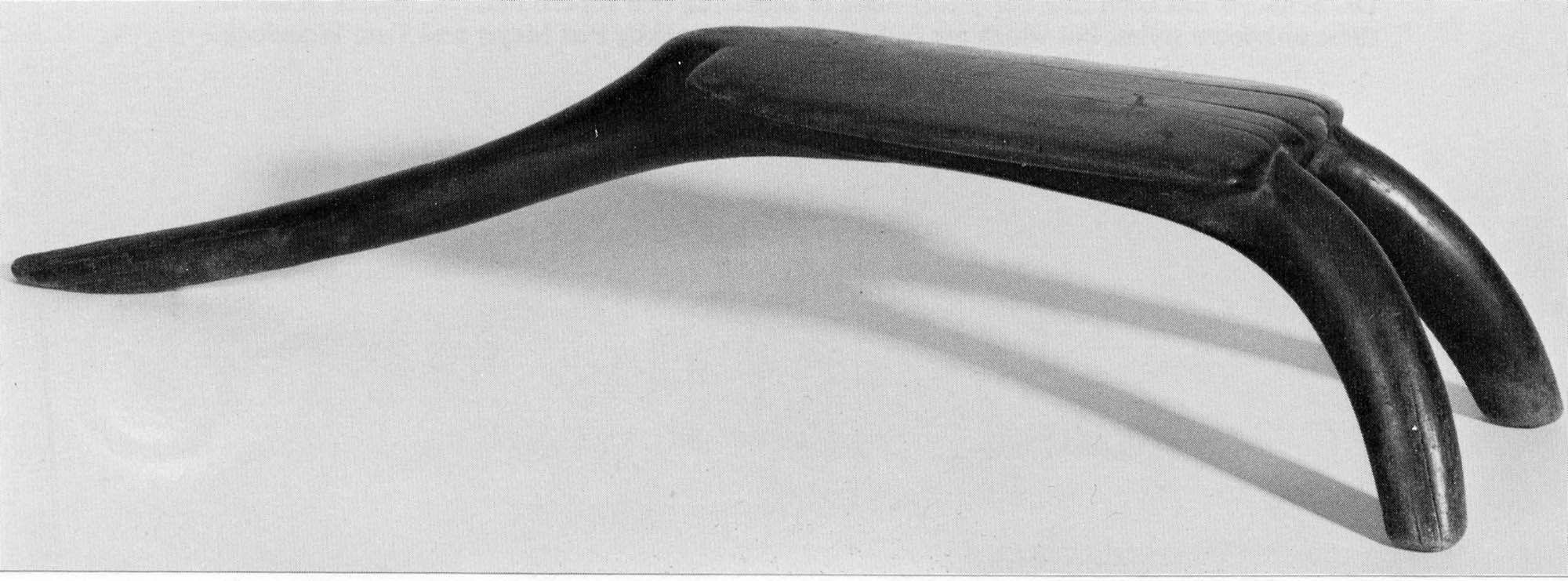

![]() Daàka, a traditional Dagara three-legged stool. Image courtesy of the Van Rijn Archive of African Art (YVRA) at the Yale University Art Gallery. Yale University Open Community Collections.

Daàka, a traditional Dagara three-legged stool. Image courtesy of the Van Rijn Archive of African Art (YVRA) at the Yale University Art Gallery. Yale University Open Community Collections.

![]()

![]()

Across Black indigenous and diasporic populations, traditional and cosmologically adapted spiritual practices — though they tend to be blanketed under the illusory, not-quite-descript and vague term of ‘Black Mysticism’ — are defined and practiced in distinctly separate ways around the world, according to the specific social, cultural and geographical contexts from which they root.

In Of Water and the Spirit, the 1994 autobiography of African author, shaman, and magic theologist Malidoma Patrice Somé, religious practice according to the Dagara people of West Africa’s Burkina Faso is the centre of focus. Presented within the context of Somé’s return to his tribal community and spiritual home, Dagara spirituality is primarily positioned as the way to come into one’s self, to fulfill the prophecy of one’s destiny as determined — in Dagara culture — by one’s name. For Somé, traditional spirituality and its appointed diviners heal and soften him, offering supernatural protections and answers on his life’s journey to fulfilling his purpose and becoming his name: “Be friends with the stranger/enemy.”

Nearly 6,500 miles from south-western Burkina Faso, in north-eastern Brazil, Afro-diasporic Angola Candomblé practices dictate a spirituality that focuses on ancestral worship in the form of nkisis. Establishing a closer relationship between human and spiritual realms, these ancestral spirit guides range from deities of abundance, the forest, and hunting, representing intelligence, discernment, and patience (Mutakalambô), to deities of an enchanted childhood, representing purity of heart, hope, and joy (Vunji). Initiates sacrifice to and call on their ordained nkisi for direction as they proceed through the seasons of life.

Back on the African continent, Lugbara spirituality in northwestern Uganda also carries deep ancestral links which establish the living and the dead as inextricably connected and in permanent relationship with one another. For its estimated one million practitioners, Lugbara is understood as a framework through which one comes to understand and rationalise life. As Ivan Karp articulates in the foreword to John Middleton’s 1960 book Lugbara Religion: Ritual and Authority Among an East African People, this is a faith that performs as “a set of beliefs and practices that people invoke to define evil, alleviate suffering, and control an uncontrollable world.” This which holds similarities, yet remains wildly different from TKTK spirituality from the TKTKT people in the Asian or Oceanic Diaspora.

Across each of these examples of Black spiritual practices — which make up just three out of the countless religious factions and sects across the African continent and its diasporic communities — the modes, means, and points of practice shapeshift, revealing ‘Black Mysticism’ as varied and non-monolithic. Yet, in each of these instances the relationship to the spiritual object remains one of the key, central, and constant elements.

Daàka, a traditional Dagara three-legged stool. Image courtesy of the Van Rijn Archive of African Art (YVRA) at the Yale University Art Gallery. Yale University Open Community Collections.

Daàka, a traditional Dagara three-legged stool. Image courtesy of the Van Rijn Archive of African Art (YVRA) at the Yale University Art Gallery. Yale University Open Community Collections.

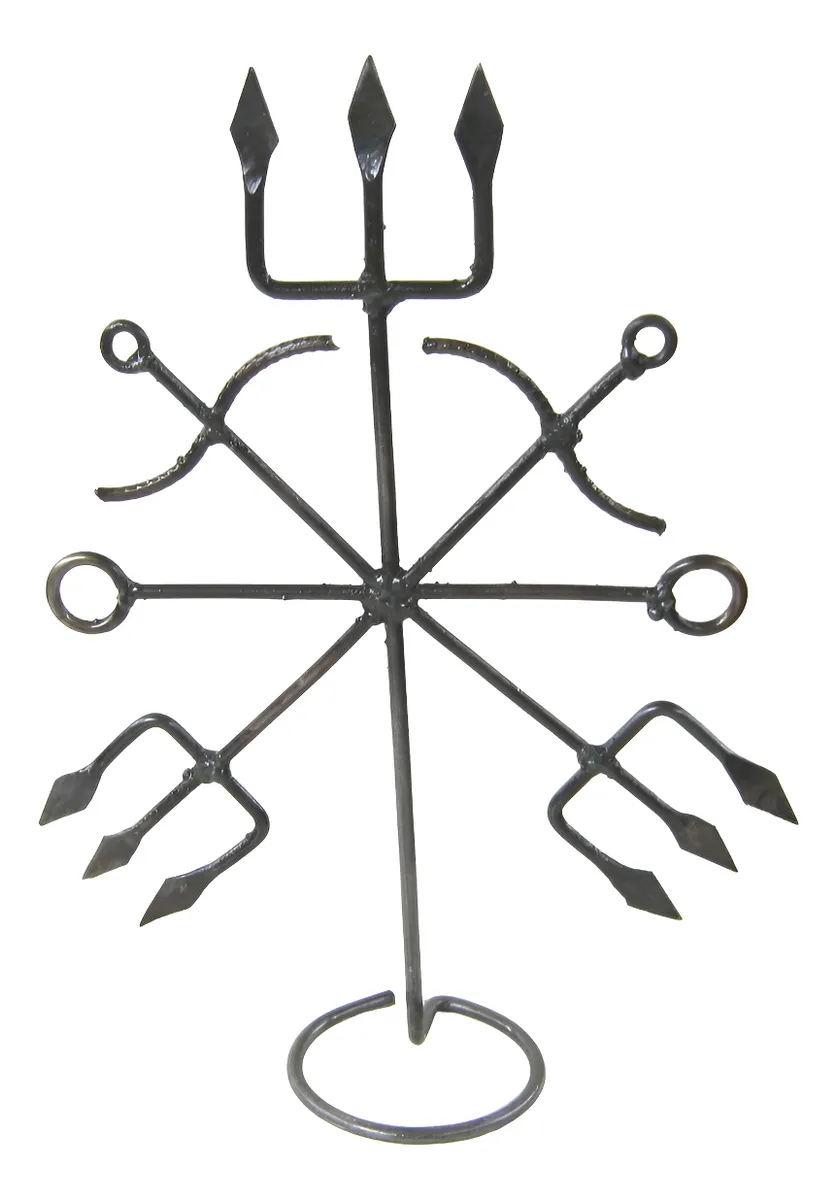

From three-legged daàka wooden stools used by the Dagara people, to the nkisi-representing ferramenta in Angolan Candomblé, and quartz stones, si, in Lugbara, the idea that spirits move and speak through material objects, manifesting themselves into the fleshly realm, is visible across numerous (if not all) of these spiritual practices. From Abrahamic religions, such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, to those that are Indigenous, pre-colonial, traditional, and cosmologically adapted, objects become the way to connect the heavens and the earth, materialising the Other World.

In order for this process to take place, a transformation must occur. Looking at religious objects in Polynesian cultural traditions, in “Containers of Divinity”, research anthropologist and Smithsonian curator Adrienne L. Kaeppler writes in a 2007 article, “Containers of Divinity”, “It is a combination of the product and the process of fabrication and wrapping that makes something sacred and divine.” Mapping these processes in the making of the “neat little ark made of sacred polished wood” that is the Tuamotu godhouse, Kaeppler deconstructs:

“Covered with fara thatch … varying in size according to the form of the god that was placed in it. One end was closed. The other end had a circular entrance for the god, with a close-fitting stopper of sacred cloth. To this ark were attached cords of sacred sennit, which were passed under it to either side, forming a loop at each corner, through which polished poles of miro wood were passed … The ark containing the god rested between.”

And for Tahitian sennit god figures (to ‘o):

“The gods were assembled, uncovered and re-dressed at a national marae ‘outdoor temple’ ... the marae was cleaned, the sacred white pu ‘upu ‘u barkcloth was prepared … cordage sacred to the god Tane was readied … the to ‘o was carried to the marae … the lesser gods were presented … The old vestments of the to ‘o were removed, placed in a sacred spot on the marae and left to decompose. The wood part of the to ‘o was rubbed … a sacred male pig was sacrificed. The to ‘o was dressed … and reactivated by incantations of the priests … all the images, to ‘o and the lesser ti ‘i (wooden images), were sanctified.”

Here, the propagation of the idea of the ritual sanctifying of spiritual objects asserts movement, via performance and order, as one of the other key elements of this spiritual/religious practice.

The construction of the Tukolor loom-shrine used by mabube weavers in Senegal’s Fuuta Toro region, can be taken as a further example (and point of escalation). Planted in a choreographed ritual detailed in Roy Dilley’s “Myth and Meaning and the Tukolor Loom” paper, the loom is built from the ground up:

“Two marks are made on the ground, one at either side of the weaver within a few inches of the end of the cloth beam.

Two more marks are made at a leg's length away from the cloth beam…These last two marks are located in the following way: the weaver, who is sitting on the cloth beam with his legs pointing out at right-angles to it, places his heels together and turns each foot with the toes outwards so that the outer-side of the foot is on the ground. At the end of each foot the weaver makes a mark on the ground…

These four marks represent the places for the four upright posts of the main loom structure.

The holes for these posts are dug in a particular order. From the weaver's sitting position they are: first, the far-right post; second, the near-left; third, the far-left; finally, the near-right.

When the weaver sinks the upright posts into the ground after digging these holes, he plants a few millet seeds under two of them — the far-right and the near-left posts.”

Transforming it into a sacred object, this ritual establishes the loom as an object of divinity and the traditional weavers as diviners. Significantly, this text also demonstrates how one sacred object begets another. For example, millet seeds — which, away from this ritual, provide sustenance as one of Senegal’s most planted and consumed crops — are buried under the front-right and back-left posts of the Tukolor loom, aiding in the transformation of the act of weaving into a practice that is spiritually fruitful and divinely guided. When dedicated under the ritual of the loom and the divinity of sacred arrangement, they turn into an utterance, a dedication, and an object of divinity. Presented before the seydaneeje spirits of the weaving craft, which occupy the loom at night, they act as a form of ritual protection and represent growth in skill.

Just as the sacred barkcloth was used in the transformation of the sacred figure and the sacred cloth in the transformation of the sacred godhouse, the sacred millet grain is used in the transformation of the sacred loom, which ancestral spirits occupy at night. Together, these objects and ritual choreographies establish the idea that not only does movement beget sanctity, and one sacred object beget another, but an object does not necessarily need to go through a process of physical transformation via ritualistic fabrication or ‘wrapping’ to be made sacred. Just as the common millet seed sees no change to its physical matter, yet is rendered as an object of divinity via dedication and sacred arrangement under divine ritual, the process of sanctity might instead be understood as first reliant on a change to the way the object is regarded by its practitioners, who, through systems of belief and worship, invite it to fall under the jurisdiction of the spiritual body.

Untitled (Movement), detail, ongoing. Graphite on paper. Angel Harvey-Ideozu.

1 Unable to put captions on the image below. Please see the caption here: Ferramenta tool in Angola Candomblé. Each tool’s design differs, depending on the nkisi it represents.

2Unable to put captions on the image below. Please see the caption here: A quartz stone representing the quartz rainstones otherwise known as si, used by Lugbara diviner rainmakers. Image via Quartz. Science Museum Group; Worcester Royal Porcelain Co. Ltd.. Open: Science Museum Group. Artstor.

2Unable to put captions on the image below. Please see the caption here: A quartz stone representing the quartz rainstones otherwise known as si, used by Lugbara diviner rainmakers. Image via Quartz. Science Museum Group; Worcester Royal Porcelain Co. Ltd.. Open: Science Museum Group. Artstor.

Credits:

Images courtesy of Angel Harvey-Ideozu

Download PDF:

Get this article in print

21 January 2026

Share: Email, Instagram, WhatsApp