Homeplace – A Love Letter

In conversation with Matri-Archi

By Angel Harvey-Ideozu

Homeplace – A Love Letter, Architekturmuseum der TUM, 2023–2024

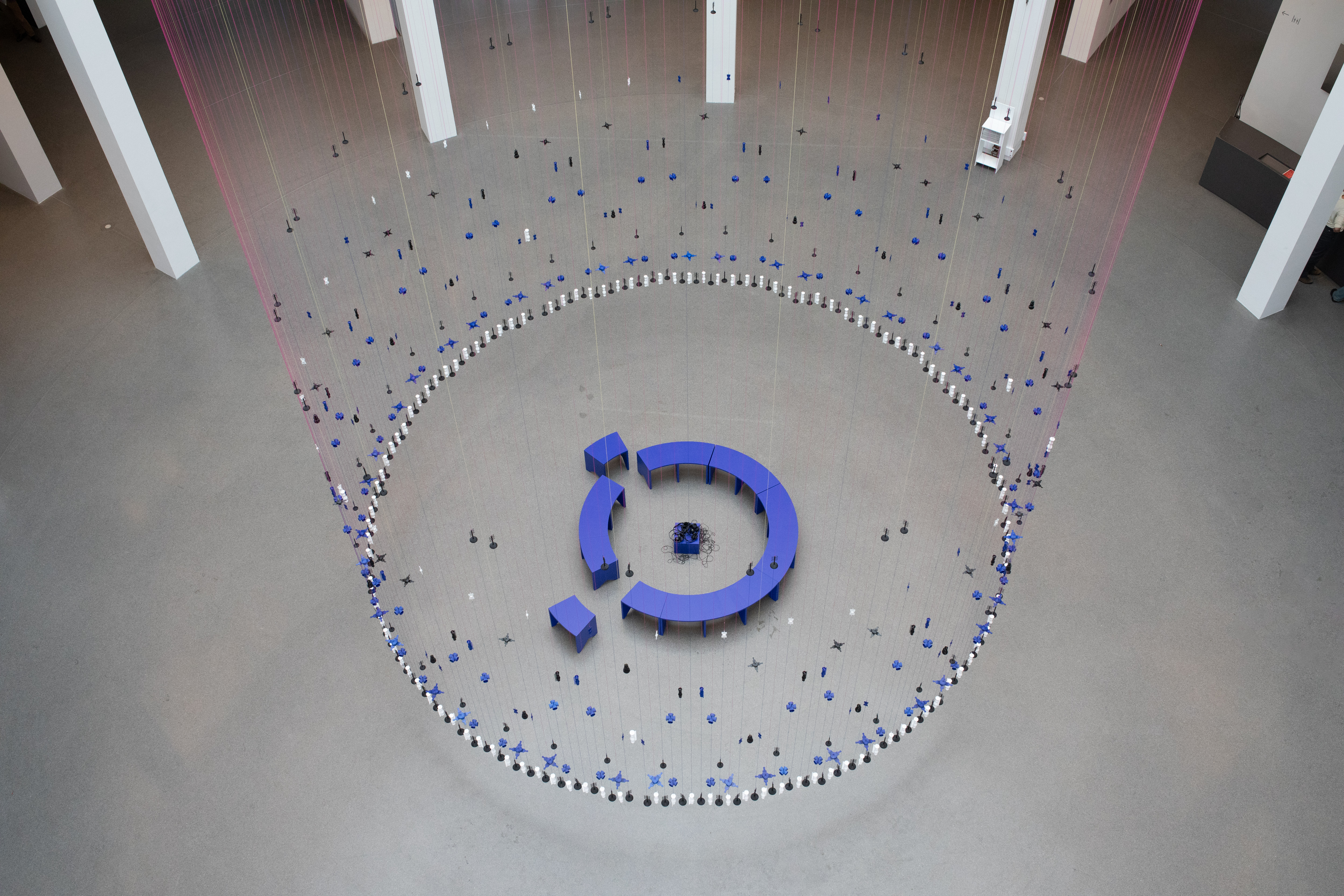

In the public Rotunda of the Pinakothek der Moderne, spatial research association Matri-Archi(tecture) installed Homeplace – A Love Letter in December 2023. An installation of ceiling-to-floor coloured threads forming a perfect circle, curved blue benches invoking an imbizo (Zulu for “gathering”), and a specially commissioned soundscape by Kenyan sound artist Kalemela, the 15-week exhibition reflected on homeplace and the spatiality of dwelling. Fluid, intimate, deeply personal yet resolutely communal, the work by Abdé Batchati, Afaina de Jong, Aisha Mugo, Khensani Jurczok-de Klerk, and Margarida N. Waco centred Afrodiasporic experiences to imagine home otherwise. For Okra Issue 1, the quintet sat with Angel Harvey-Ideozu to speak about bell hooks, desire as a prompt, navigating institutions, the role of the exhibition newspaper, and African timing.

Angel Harvey-Ideozu:

Let’s start by talking about desire. The show has been described as emerging from a “deep desire to expand and create a culture of exchange, gathering, joy, and return.” Why was it important to insist on desire in this context?

Khensani Jurczok-de Klerk:

Desire is central both to bell hooks’ thinking and to Matri-Archi’s relational practice. Desire is not only an impetus to work but a design premise for being in the world beyond material conditions that often exclude racialised people from desiring. Dreaming becomes a survival strategy. Oppressive systems cannot possess spectral values like song, ritual, recipe, or oral history. These are what we carry, and they shape how Homeplace took form.

Aisha Mugo:

Collectively, the desire was to bring home and what is special to us, into this clinical space. When we were approached to do [Homeplace], we had this desire to bring ourselves — all of our selves: our histories and geographies especially, into the space of the rotunda. Together, we represent Kenya, Togo, Cabinda, Suriname, and South Africa. We wanted to bring and question how to manifest that physically in a space that maybe hasn’t been very kind to Black women or to diasporic people in general, regardless of creed.

Homeplace – A Love Letter, Architekturmuseum der TUM, 2023–2024

AHI:

This is a show that the audience partakes in and it’s all quite communal, but it’s also very personal and private, or at least has the potential to be, especially with the sound playing in individual headphones. Did you want the visitors feeling like they had just left a public homeplace or a private one? And what would have been the difference?

AM:

I can’t say either or, because I think there’s something really interesting about the way in which we read homeplace as a prompt to think about some sort of construction in cultural belonging that is not fixed in time, pace, or form. So, in a way I think that that space in the rotunda that we activated demanded a certain kind of negotiation, as the curtain did. We got super excited about the curtain as an archetype, not only because it’s something that’s familiar to all of us in the geographies that we’re from and call home, but because it’s also a sort of tenuous and sensitive archetype that offers room for choice. You can see someone approaching the curtain, because it’s normally not completely opaque. If it is opaque visually, audibly it still suggests when someone walks in. These were really interesting design prompts for us to consider the form of the curtain itself.

Unlike a door which only has a shadow when it’s open, the curtain always has a shadow. It’s also very thin and tenuous, and doesn’t have a lock, which becomes this set of negotiations and relations that one has to work through. [Where the curtain divides the kitchen from the living space and] there is a productive gossip happening in the kitchen, a decision is made by the people there to either open up that gossip to whoever they see is approaching through that curtain, or safeguard that information by completely changing the logic of the conversation in that room. In that way, [with the curtain Homeplace,] there was always a public component to it in that it offered an entrypoint to those who might have been familiar with it, could see, or approach it. But there was also a private-facing component that safeguarded it from being tampered with, co-opted, and interrupted. It maintained it as some sort of safe space, if you like, but of course that was always fluid and moving.

Unlike a door which only has a shadow when it’s open, the curtain always has a shadow. It’s also very thin and tenuous, and doesn’t have a lock, which becomes this set of negotiations and relations that one has to work through. [Where the curtain divides the kitchen from the living space and] there is a productive gossip happening in the kitchen, a decision is made by the people there to either open up that gossip to whoever they see is approaching through that curtain, or safeguard that information by completely changing the logic of the conversation in that room. In that way, [with the curtain Homeplace,] there was always a public component to it in that it offered an entrypoint to those who might have been familiar with it, could see, or approach it. But there was also a private-facing component that safeguarded it from being tampered with, co-opted, and interrupted. It maintained it as some sort of safe space, if you like, but of course that was always fluid and moving.

Margarida N. Waco:

You’re right in pointing to this oscillation between communal publicness and private introspection, between being together and turning inward. What held Homeplace together was not a single idea of home, but four different ways of arriving at it, with each asking for something slightly different from us. It felt significant that this movement runs through the four elements we introduce that speak to the multi-sensory experience of the exhibition. First, the beaded curtains; second, the imbizo benches — a key figure among many African traditions; third, the newspaper; and, finally, the soundscape. Rather than relying on a singular participatory logic, the work was shaped by these coexisting modes held in relation to one another.

While the imbizo allowed for co-presence without obligation as one could sit together, quietly or in conversation, the newspaper introduced circulation. Unlike the curtain, which marked a durational threshold, or the act of sitting together, which happened in the moment, the newspaper we developed with graphic designers and illustrators Sherida Kuffour and Jehane Yazami was meant to move. Its temporarility is different as it extends Homeplace beyond the exhibition space and into other contexts and conversations. The soundscape we commissioned from Kenyan sound artist Kalemela, on the other hand, offered the most intimate form of encounter as it was played through headphones. It drew listeners inward and asked for a different kind of attention. These four modalities together do not necessarily resolve whether Homeplace is public or private alone, but keep that question open. Each one carries a different way of being with others: approaching, sitting, carrying, listening. None claim the final word. In this sense, the work is likely less about leaving a public or private space behind and more about noticing how easily the two move and thread into one another and how much care is needed to navigate what lies in between.

While the imbizo allowed for co-presence without obligation as one could sit together, quietly or in conversation, the newspaper introduced circulation. Unlike the curtain, which marked a durational threshold, or the act of sitting together, which happened in the moment, the newspaper we developed with graphic designers and illustrators Sherida Kuffour and Jehane Yazami was meant to move. Its temporarility is different as it extends Homeplace beyond the exhibition space and into other contexts and conversations. The soundscape we commissioned from Kenyan sound artist Kalemela, on the other hand, offered the most intimate form of encounter as it was played through headphones. It drew listeners inward and asked for a different kind of attention. These four modalities together do not necessarily resolve whether Homeplace is public or private alone, but keep that question open. Each one carries a different way of being with others: approaching, sitting, carrying, listening. None claim the final word. In this sense, the work is likely less about leaving a public or private space behind and more about noticing how easily the two move and thread into one another and how much care is needed to navigate what lies in between.

AHI:

What safeguards were put in place to prevent that co-option Aisha spoke about?

Afaina de Jong:

To take it back to what Khensani was saying earlier, of course the installation was a public space, but it was made up of elements that come from private spaces and from our private homes and histories of migration. From Suriname to Kenya, we took objects that were very dear to us and merged them together. In that sense, the objects are part of our inner worlds. [So although we inhabited] this white cube, public space, the elements are ‘home’, and they’re very hard to co-opt in that sense, and because they are from our imaginaries in how we put them together. Yes, anyone could have been in the space and a museum can co-opt our narrative in the sense that they look great inviting us, but what we put there is the story that we wanted to tell, and we worked on that quite separately from the institution. It’s really something we did as a collective, then, all of a sudden, it was there, [in the Architekturmuseum der TUM]. [Laughs.] And maybe it was good that there wasn’t a creative back and forth between them and us.

Details of Homeplace – A Love Letter, Architekturmuseum der TUM, 2023–2024

AHI:

The abstraction of the objects that make the curtain really stand out. First of all, it’s just absolutely beautiful. But further than that, to me, it really encapsulates this notion that homeplace — and what makes it — is not fixed in form, but non-linear and fluid. Can you guys talk to me about that choice to abstract?

AB:

For me, the abstraction that happened was quite an intuitive process from being in conversation with each other. Collectively, we created this matrix where we all collected different objects and talked about the stories that we connect with them. There were already relations between us, but it also started to build between the objects. What’s really lovely about that process too, is that aside from us putting these objects together and transforming them, this is what happens in real life: people take objects with them, they live with objects, they interact with objects. And the objects change form and break and get repaired.

AM:

Collectively, the desire was to bring home and what is special to us, into this clinical space. When we were approached to do [Homeplace], we had this desire to bring ourselves — all of our selves: our histories and geographies especially, into the space of the rotunda. Together, we represent Kenya, Togo, Cabinda, Suriname, and South Africa. We wanted to bring and question how to manifest that physically in a space that maybe hasn’t been very kind to Black women or to diasporic people in general, regardless of creed.

Details of Homeplace – A Love Letter, Architekturmuseum der TUM, 2023–2024

AHI:

The act of building a homeplace can sound quite beautiful or romantic, and can render an idealised version of home as perfect. However, the reality of home, which the group notes, is not always positive. As Ókólí Stephen Nonso writes in the exhibition’s newspaper, home can be “a noose,” “a sad place,” “a midwife aborting dreams.” How did you balance the reality of home and that of recovering home when away from it, in the construction of the rotunda?

AM:

I think this is why the newspaper is so important. It was so important to us to have something that reflected realities beyond ourselves by reflecting the realities of various writers and thinkers who have continuously contested with the notion of home. And for me, it was about making sure we got all those voices into something tangible. The exhibition will come and go and we will remain with the feelings, but we had to make sure there was a takeaway that people could pass on between one another, between lovers, between friends, enemies, colleagues. It is something that will live beyond us and we don’t know whose hands it’s going to fall into, but perhaps it falling into someone’s hands would give it that solace and comfort that it might be seeking outside the rotunda.

AB:

For me, growing up in a place like Munich, where I wasn’t surrounded by a lot of black people, I read a lot of Black German [literary] figures, which was so important for me and gave me a lot of what I was needing. Being able to read from someone you don’t know but you can relate to is really powerful. I think it’s really lovely that the newspaper can be exactly that for another person.

KJK:

I think what Homeplace offered us was a prompt to think about homeplace as a practice, rather than a fixed site. In that regard, maybe the more implicit question that was there but we never really vocalised, was how, if at all, is architecture a helpful category for thinking about home. Because traditionally within the western project, architecture considered home as something attached to property, which presumed a fixed ownership and the idea that you accumulate within the boundaries of that place. Which turns into a larger conversation around collection, inheritance, hegemony, and power. Whereas there are perhaps different ways of thinking about constructing cultures of belonging and home outside of those fixed principles, whilst still drawing from a lot of the creative principles architecture has to offer. Luckily, there are so many practitioners and scholars right now, who share some of those questions we have around, “What actually is a decolonial practice?”.

MNW:

What the newspaper and the soundscape hold for me in particular is how the voices and texts gathered allowed us to segway into the ambivalence and contradiction you’re pointing to. As Aisha said, the newspaper assembled writers that contest home from many positions, tracing the ambivalence between its comforts and its violences without resolving it. The soundscape moved alongside this differently: through fragments of memory, grief, but also humour. And in staying with that tension, neither of the formats flattened home into sanctuary or suffering alone, but instead, offered space to sit with and recognize its multi-layered complexity and reality. And I think this is crucial to think about home not as a fixed place, but as something that is continually practiced, rehearsed, and mediated over time — to echo Khensani.

Homeplace – A Love Letter, Architekturmuseum der TUM, 2023–2024

AHI:

You guys ultimately come to a definition of homeplace as a site of return and recovery. The ‘re’ prefix is intriguing. It sites homeplace as a place you can “go back” in, which instigates a temporal dimension. Home can be argued as the one place where time isn’t linear, regardless of context. Even in the West, at home, time resists those Western notions of itself. What do you make of that?

KJK:

I don’t think home is the only place where the logic of time can be interrupted. But I think to think about time is to think about place, and the homeplace. Maybe it’s a personal insertion, but I think that it offers a different understanding of pace. Essential to recovery and restoration is the understanding of slowness. It’s a refusal to adhere to the fastness and the pace of life outside of the homeplace, which often contorts us in ways that makes life unlivable, and forces us to labour in ways that perhaps are not desired. The homeplace which is set up on relations and manifests in fellowship and commune with others, is therefore set on a series of rituals, ceremonies, behaviours that constitute their own pace. That is something I find special. It’s very difficult though, because is that something that can be articulated spatially? Yes. But can it be articulated as a fixed space? I’m not quite sure. I think this is also what our space did. It was not fixed in that regard.

AM:

I would like to call upon African timing. What it invokes is an invitation to stay a while. Your mum tells you, “One more hour, I promise we’re going.” But you’re still at your aunt’s house three hours later. But you’re running around, playing with your cousins, falling asleep, eating, doing whatever. So I think the installation itself, and what the team has said about dwelling, is an invitation to come in, to stay, discuss and gather. That in itself suspends the notion of time. The clock is still ticking, but in that moment time is suspended, and the body, the mind, and the self completely disconnect from the outside world and the demands that it brings forth.

Credits:

Homeplace – A Love Letter, 2023–2024.

© Matri-Archi(tecture), Architekturmuseum der TUM.

Photography: Ulrike Myrzik.

Download PDF:

Get this article in print

21 January 2026

Share: Email, Instagram, WhatsApp