No Lubida Mi

The monobloc not just as an object, but as a quiet witness to belonging, memory, and cultural continuation.

By Lilly Alexandra

The Monobloc chair.

That white plastic chair.

We all know it. You might own one, or even a couple. Pressed from a single piece of plastic, it is one of the most recognisable chairs in the world and one of the most debated objects of modern design. Cheap, mass-produced, nearly indestructible. Loved and loathed in equal measure.

I understand the criticism. The chair is everywhere, difficult to escape, cluttering landscapes across the globe. But those same qualities are precisely why it has become so embedded in life on the ABC islands. The Monobloc is resilient. It withstands heat, rain, hurricanes, and salty sea air. It stacks easily, stores neatly, and survives endless use. You will find it at family gatherings, birthday parties, roadside domino games, wakes, political speeches, church events, and school fairs. There is almost always one nearby.

My relationship with the chair didn’t begin in theory. It began with observation, with what I kept noticing every time I returned home.

Every few years, I return to the ABC islands. I spend time watching how people move through space, how objects are used and reused. One day, I noticed two Monobloc chairs stacked on top of each other at the side of the road. Both were broken. Together, they formed one usable chair again. That moment marked a shift in how the chair could be understood.

This gesture goes beyond resourcefulness. It reflects a design logic shaped by survival and care, by generations of making things last and making them matter. In a history where land, language, and identity were never disposable, neither were objects. Reinvention, repair, and reuse were not aesthetic choices, but necessities. Caribbean life has always insisted on continuity under impossible conditions.

From then on, the chairs began to appear everywhere. Alone or clustered, pulled into the shade, flipped upside down to dry after rain. They don’t just mark where something happened; they hold traces of it. A chair by the roadside suggests someone sitting, waiting, thinking. Another person passes, they greet, maybe they sit too. What was solitary becomes shared.

These arrangements follow their own rhythm. Casual, familiar, but full of meaning. Even when I arrive after the gathering has ended, I can read the scene through the chairs. For me, their placement often tells more than photographs ever could. Through their stillness, they speak.

Returning home can feel like stepping into something mid-conversation. Familiar, but slightly out of sync. There is comfort in sitting in the same chairs, easing back into a rhythm that continued in your absence. Even briefly, you become part of something ongoing: everyday rituals that hold culture together.

The Monobloc becomes more than a seat. It becomes a quiet structure for oral tradition to continue, a support for memory, gathering, and relation.

Chairs that hold people.

People that hold stories.

Stories that hold culture.

Sculpting memory into form

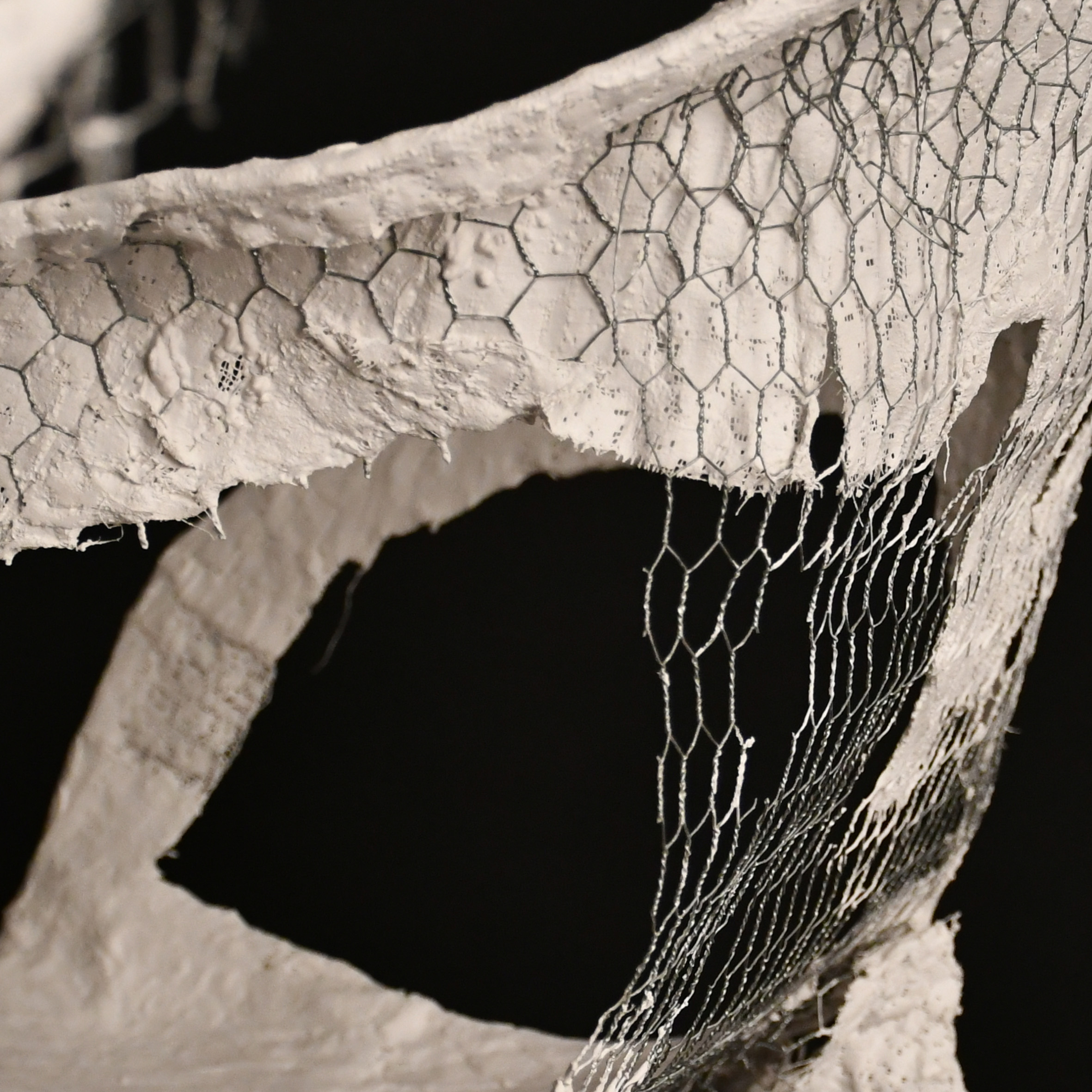

This research explores how the Monobloc chair, often dismissed as a generic global object, operates as a carrier of cultural memory and resilience on the ABC islands. Through sculptural reinterpretations made from chicken wire and plaster, the work reflects on how culture is preserved through repetition, relation, and everyday use rather than formal institutions.

The sculptures echo the chair’s presence in communal life. They reference roadside gatherings, family events, and informal spaces where stories circulate. Here, design, memory, and oral tradition intersect as acts of resistance against erasure.

Chicken wire is a material deeply tied to home. I remember it from my grandmother’s yard, curled in corners, holding something in or keeping something out. On the islands, it appears everywhere: fencing gardens, reinforcing enclosures, patching boundaries.

During the making process, I returned to Édouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation. The wire’s interlaced structure began to mirror the ideas Glissant describes: strands crossing without merging, distinct yet dependent on tension and relation. The material holds its form by connecting. It is open without collapsing. To me, this flexibility without loss became a tangible expression of Caribbean identity, formed through movement, friction, and continuity over time.

Introducing plaster shifted the language of the work. Applied slowly over the wire frame, it softened the form, added weight, and created a sense of protection. But as it dried, cracks appeared. Small fractures formed, and in places the wire began to push back through.

Unlike plastic, plaster does not pretend to last forever. It carries its fragility on the surface. This vulnerability became central. Where the wire speaks of resilience and connection, plaster reveals erosion and the risk of forgetting. Like oral tradition, it requires care, repetition, and presence to survive.

Still, even as the surface cracks, the structure remains. What fades makes visible what endures.

The original Monobloc resists time. It refuses decay. These sculptures allow for change. They make space for softness, vulnerability, and transformation. Memory here does not survive by resisting time, but by moving with it.

Placeholders of memory

The installation space is arranged to echo how chairs appear in daily life. Not aligned or frontal, but scattered, paired, angled as if mid-conversation. Some slightly tilted, others clustered, as though people have just stepped away.

Gatherings in Caribbean life are rarely formal or fixed. They emerge wherever space allows: backyards, roadsides, verandas, church halls. The Monobloc adapts to this. It does not impose structure; it responds to the lives around it.

By recreating this kind of setting, space is held for what happened there. For conversations that linger. For silences that feel full. There is no single focal point. The installation is meant to be moved through, like arriving at a gathering where the voices have quieted but the atmosphere remains.

To migrate is to carry memory across water. Not just objects, but gestures, rhythms, and stories that were never written down. On the ABC islands, oral tradition was a necessity. Under colonial rule, language and archiving were controlled. What could not be recorded had to be remembered, held in the body, the voice, the gathering.

Now living in the Netherlands, the settings change. The chairs move indoors. The materials shift. But the practice continues. Each return carries something back, and each departure brings something forward.

No lubidá mi means “don’t forget me.”

For me, it is not nostalgia, but commitment.

To speak, to gather, to remember.

The chairs may disappear.

The settings may shift.

But the act of holding space for one another continues.

To say no lubidá mi is not a plea.

It is a promise.

Credits:

Images courtesy of Lilly Alexandra

Download PDF:

Get this article in print

21 January 2026

Share: Email, Instagram, WhatsApp