How long have we known each other now? About ten years? We started working together at COS in retail. That job was actually quite formative, all the trend forecasting, style meetings, folding trousers while talking about our future careers. How has having a design community shaped your practice? Do relationships, friendships, collaborations help unlock new ways of expressing yourself through design? And why do you not have a collection named after me yet, because you love me so much?

On Memory, Material, and Community

A conversation between Kusheda Mensah and Bianca Saunders

By Kusheda Mensah & Bianca Saunders

Kusheda Mensah and Bianca Saunders first crossed paths over a decade ago while working in retail at COS. What started as long conversations about silhouettes, materials, and future ambitions on the shop floor slowly grew into a lasting creative friendship. Today, their practices span fashion, furniture, and spatial design. Both are shaped by cultural heritage, community, and a shared belief that design is as much about people as it is about objects. In this conversation, they reflect on their early days, talk about how Jamaican and Ghanaian influences shape their work, and explore how memory, translation, and togetherness continue to inform their approach to design.

Kusheda Mensah:

Bianca Saunders:

(laughs) Yes, about ten years! From those COS days, always obsessing over silhouettes, palettes, and cuts. Even then we were already designers at heart. Beyond work, we stayed in touch through friends and our creative circles, which was so affirming. Having people who get it has been essential. The jokes, the accountability, the sharpness. Collaborations and friendships keep me playful but grounded. And you are definitely the inspiration behind some pieces. I just have not put your name on the label yet.

KM:

I was kidding, but maybe not. Honestly, those friendships gave me confidence in my own design voice. Retail taught us to read people’s taste, how they present themselves. That is why I have always trusted your eye. You care deeply about design and how you show up. It motivates people around you. Friendships like ours sharpen you and remind you that design does not exist in isolation. Community is at the heart of my work, whether it is Ghanaian culture or our London creative scene. You are a big part of that. And yes, you are due a collection naming soon.

KM:

Are there specific objects from the Jamaican influences in your home growing up, like furniture, clothing, or even textures, that shaped your design vocabulary?

BS:

Absolutely. My grandma’s glass-wood cabinet, kept in the front room and only opened on special occasions. Textured wallpapers that felt like fabric. Plastic-covered sofas. Everything was about preservation and presentation. That blend of utility and style really stayed with me. In contrast, my parents’ home was minimalist and modern. I grew up negotiating between tradition and simplicity, and that duality still shows in my work, in the materials, cuts, and layering I use.

KM:

I can see that duality in your practice. For me, stools were central to my Ghanaian upbringing. In Asante culture they are symbols of authority and ancestry, but in my house they were everywhere, for cooking, as side tables, even in the bathroom. That everyday versatility shaped how I think about furniture. My mum also loved collecting masks, sculptures, Ghanaian textiles. Those objects were anchors to Ghana. Textiles especially felt like a non-verbal language, carrying history without words.

At the same time, she was inspired by what she saw as the quintessential English home, floral walls, presentation, almost like a toned-down Mrs. Bouquet from TV. So our house became a hybrid of African heritage and English ideas of presentation. That duality shaped how I see design. My work always tries to hold more than one purpose.

At the same time, she was inspired by what she saw as the quintessential English home, floral walls, presentation, almost like a toned-down Mrs. Bouquet from TV. So our house became a hybrid of African heritage and English ideas of presentation. That duality shaped how I see design. My work always tries to hold more than one purpose.

KM:

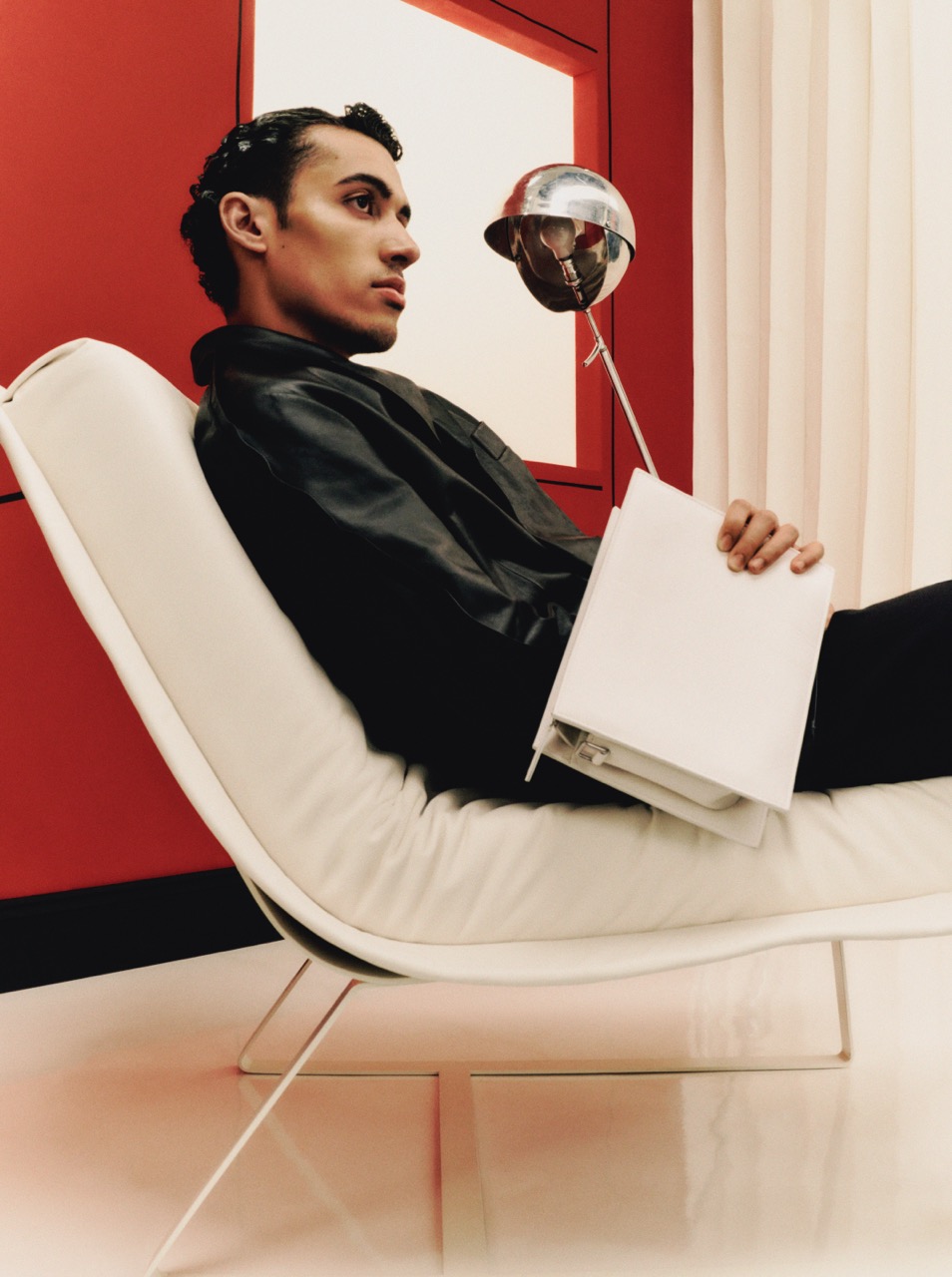

When you worked on your ECCO furniture collaboration, how did your approach shift from designing for the body to designing for the room?

BS:

With fashion, I am always thinking about how something moves with the body. With furniture, the body became the room, or more precisely how people use it, how they lean, gather, or rest. I became fascinated with how things slouch into corners and how softness and structure can live together. The biggest shift was pace. Fashion is seasonal, fast, fluid. Furniture has permanence. It stays with you. Still, I begin with emotion and narrative. What feeling do I want to create? What interaction am I inviting? From there, forms take shape.

KM:

I also start with a feeling, often through colour, how a shade makes me feel and what atmosphere it creates. Then I imagine the people in that space, friends, family, our creative circles. Design should be tactile and sensory, something you want to touch, lean into, gather around. Once the feeling and colour are set, that dictates fabric, then form. The shapes are always in service of interaction, closeness, conversation, intimacy.

KM:

When you bring Jamaican cultural references into your work, do you see it as preserving an archive, or reimagining it into something new? And how does community play into that?

BS:

There is always tension between honouring and evolving. Much of what inspires me comes from memory, rituals, family, but I do not want to just replicate. For me, it is translation rather than nostalgia. A way of keeping traditions alive while letting them adapt to now. My family is central to this. My grandma has a huge family, all the grandchildren and great-grands adding their own spin. Their interpretations, reactions, even criticisms all help me reshape my work.

KM:

I have also been thinking about this. For a long time, I resisted obvious gestures, like covering a chair in African print fabric. It felt performative, playing into Western expectations of what African design should look like. Instead, I am interested in translating the essence of my heritage, how gatherings look and feel, the multifunctional use of objects, the non-verbal language of textiles. These become contemporary forms that are still rooted.

I have realised that I am Ghanaian, so whatever I create carries that inherently. British too, but always Ghanaian at heart. My work carries forward fragments of memory, material logic, and social practice, remixed into new shapes for today’s spaces. The balance between memory and invention is always ongoing.

I have realised that I am Ghanaian, so whatever I create carries that inherently. British too, but always Ghanaian at heart. My work carries forward fragments of memory, material logic, and social practice, remixed into new shapes for today’s spaces. The balance between memory and invention is always ongoing.

Images courtesy of Kusheda Mensah and Bianca Saunders.

Download PDF:

Get this article in print

21 January 2026

Share: Email, Instagram, WhatsApp