Sucking Salt: Architecture in a Third Culture Sphere

Ten Buildings in Curaçao

By Zenobia Lee & Shani Strand

Sucking Salt is an ongoing research project that focuses on archiving Caribbean architecture and aesthetics. It seeks to expand architectural history by positioning the Caribbean not as a peripheral footnote, but as a site of material, cultural, and historical significance. As a region shaped by layered colonial histories and migrations, the Caribbean offers a unique lens through which to understand how architecture becomes a space where multiple cultures meet, adapt, and transform one another.

Sylvia Wynter describes the historical trajectory of the Caribbean as a “third culture sphere”: neither Latin nor Anglo-Saxon, but a syncretic Euro-African or Afro-European continuum that also incorporates Central America. Within this context, cultural syncretism can be understood as a process of exchange and adaptation that emerged through contact between Indigenous, European, and African peoples in the so-called New World, resulting in new, hybrid cultural and material expressions.

Curaçao holds a particular place within this history. As one of the most significant locations in the Dutch participation in the Transatlantic Slave Trade, the island bears deep traces of these entangled histories in its built environment. West African aesthetics, for example, left a lasting imprint on the island’s architecture, especially in the kunuku houses that were originally built as slave dwellings by enslaved West Africans. Alongside this, vernacular architectures developed outside of colonial styles, forming parallel architectural lineages.

During the nineteenth century, Curaçao experienced an influx of migrants from Europe, South America, and other parts of the Caribbean and Africa. This resulted in increasingly eclectic architectural expressions that combined elements of Dutch, Spanish, French, and Caribbean traditions, often characterized by bright colours and ornamental details. Like much of the Caribbean, many architectural styles were developed in the colonial core and adapted to local climate, materials, needs, and aesthetic languages. This process of exchange and adaptation has shaped the island’s built environment over time.

In the following images and descriptions, Sucking Salt presents a selection of ten buildings across Curaçao that exemplify these processes of syncretism and cultural exchange. The selection spans a wide range of architectural expressions, from art deco and brutalism to vernacular structures in both historical and contemporary forms, as well as the use of natural materials such as wattle and daub or sand. Read together, these buildings form a web of aesthetic collisions, mirroring the collisions of cultures both parallel and distinct.

Landhuis Ascension

Weg naar Westpunt, Barber, Curaçao — 1672

Landhuis Ascension is one of the oldest surviving plantation houses in Curaçao, built in 1672 on the site of a former indigenous Caquetío village known as Pueblo de la Madre de Dios Ascención. The estate was founded by Jurriaan Janszoon Exteen and forms part of the early colonial plantation system that structured the island’s agricultural and social landscape. Today, the complex is owned and used by the Royal Dutch Navy.

The building has a rectangular floor plan with adjoining galleries and is characterized by a steep hipped roof, gables, sash windows and shutters, a triangular pediment, and classical cornices. It was constructed using local materials, including fossilized coral stone. The landhuis exemplifies Dutch colonial plantation architecture and illustrates how European building traditions were adapted to local materials and climatic conditions.

Details

Location: Weg naar Westpunt, Barber, Curaçao

Date: 1672

Architect: Unknown

Type: Plantation house / landhuis

Current use: In use by the Royal Dutch Navy

Source

https://evendo.com/locations/curacao/westpunt/attraction/landhuis-ascencion

Kas di Pal’i Maishi (Kunuku House)

Dokterstuin 27, Ascencion, Willemstad, Curaçao — 19th century

Kas di Pal’i Maishi is a traditionally restored nineteenth-century cottage that currently functions as a museum focusing on the heritage of Afro-Curaçaoan communities between 1850 and 1950. The house represents a type of rural dwelling built outside the colonial architectural tradition and offers insight into how Black communities in rural areas lived during and after the period of enslavement.

The building is characterized by tapered walls constructed with wattle and daub, rubble stone with clay plaster finishing, and a thatched roof made from palu’i maishi (sorghum leaves). The floor is sealed with a mixture of clay and cow dung, while the roof structure is formed from tree branches used as rafters and purlins. These construction methods and materials demonstrate a vernacular building tradition shaped by local resources, climate, and necessity.

DetailsLocation: Dokterstuin 27, Ascencion, Willemstad, Curaçao

Date: 19th century (circa)

Architect: Unknown

Type: Kunuku house / vernacular dwelling

Current use: Museum

Source

Association of Museums and Heritage of Curaçao

https://museumsofcuracao.com/museum/museum-kas-di-pal-i-maishi/

Kas di Kanchi

Frederikstraat 113, Willemstad, Curaçao — second half of the 19th century

Kas di Kanchi is a late nineteenth-century town house that represents a rare example of gingerbread-style vernacular architecture in Curaçao. While this architectural language is widespread in other parts of the Caribbean, it remains exceptional on the island, making this building a distinctive presence within Willemstad’s historic urban fabric. The house reflects the circulation and local reinterpretation of Victorian and Gothic-inspired architectural motifs within a Caribbean context.

The building is characterized by a U-shaped verandah with ornate gingerbread fretwork and a steep roof. These decorative wooden elements introduce a light, expressive layer to the façade while also serving climatic and social functions, mediating between interior and exterior space. Kas di Kanchi exemplifies how imported stylistic vocabularies were selectively adapted and absorbed into Curaçao’s vernacular building traditions.

DetailsLocation: Frederikstraat 113, Willemstad, Curaçao

Date: Second half of the 19th century

Architect: Unknown

Type: Town house / vernacular dwelling

Current use: Not specified

Source

https://curacaomonuments.org/sites/frederikstraat-113/

Willemstad Color Scheme Myth

Willemstad, Curaçao — 1816–1819

In the early nineteenth century, Willemstad’s urban appearance changed radically when Governor Albert Kikkert ordered the city’s white buildings to be repainted in colour. Officially, the measure was justified as a medical necessity: Kikkert suffered from migraines, which his doctor attributed to the intense reflection of sunlight on white façades. Property owners were therefore required to repaint their buildings, permanently transforming the city’s visual identity.

In 1819, it was revealed that Kikkert held shares in the island’s only paint factory, from which all building owners were obliged to purchase their paint. The regulation thus combined colonial authority with private economic interest, turning what is often seen today as a picturesque urban feature into the result of a calculated and contested intervention.

DetailsLocation: Willemstad, Curaçao

Date: 1816–1819

Initiator: Albert Kikkert, Governor of Curaçao, Aruba and Bonaire

Type: Urban regulation / transformation of cityscape

Current status: Ongoing defining feature of Willemstad’s urban identity

Source

Traditional historical account of the Willemstad colour scheme (various local histories and archives)

Bargestraat 52–54

Bargestraat 52–54, Willemstad, Curaçao — circa 1930s

The buildings at Bargestraat 52–54 form a modest but expressive example of early twentieth-century vernacular architecture in Willemstad. Dating from the 1930s, the ensemble reflects the everyday urban fabric of the city rather than its monumental or representational architecture, showing how international influences and local building traditions were combined in ordinary residential or mixed-use structures.

The complex is characterized by its colourful exterior, a gable roof on the east side and a slanted roof on the west, ornamental infill in the gable, four-blade windows, and modelled stonework. It is constructed using traditional materials such as concrete masonry, wooden window frames, and Dutch roof tiles. Together, these elements demonstrate a pragmatic and hybrid architectural language rooted in local building practice.

Details

Location: Bargestraat 52–54, Willemstad, Curaçao

Date: Circa 1930s

Architect: Unknown

Type: Vernacular urban building

Current use: Not specified

Source

https://curacaomonuments.org/sites/bargestraat-52-54/

KNSM – Koninklijke Nederlandsche Stoomboot-Maatschappij n.v.

Breedestraat 39, Punda, Willemstad, Curaçao — 1939–1941

The KNSM building was constructed as the head office of the Royal Netherlands Steamship Company, a key player in the maritime networks connecting Curaçao to the Netherlands and the wider Atlantic world. Although the architect is unknown and the building is often attributed to Gerrit Rietveld, its formal language shows a clear affinity with Dutch interwar architecture. Curaçao-based architect Ronny Lobo has noted its resemblance to Willem Dudok’s Town Hall in Hilversum (1931), particularly in its massing and use of specially produced ochre-coloured bricks imported from the Netherlands.

The building is characterized by a square tower, unplastered brick façades, a steep beveled roof, and bronze window frames. The west façade originally featured black marble slabs and stained-glass windows, underscoring the representational and corporate character of the building. Combining modernist massing with elements associated with Art Nouveau and Dutch brick expressionism, the KNSM building exemplifies how European architectural idioms were transplanted and recontextualized in Curaçao’s colonial urban landscape.

Details

Location: Breedestraat 39, Punda, Willemstad, Curaçao

Date: 1939–1941

Architect: Unknown (often attributed to Gerrit Rietveld)

Type: Office building / corporate headquarters

Original use: Head office of the Koninklijke Nederlandsche Stoomboot-Maatschappij n.v.

Source

KNSM-gebouw, Willemstad (1941) – Dudok.org

https://ellenevenhuis.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/amigoe-c3b1apa-docomomo-1-2010-02-27.pdf

Cinelandia Cinema (formerly Bioscoop Cinema)

Hendrikplein Z/N, Punda, Willemstad, Curaçao — 1941

Cinelandia Cinema was built in 1941 as an open-air movie theatre and, at the time of its opening, was the largest cinema in the region. The building was designed by Pieter A. van Stuivenberg, a Dutch designer who was not formally trained as an architect but was responsible for several utility buildings in Willemstad. As a place of mass entertainment, Cinelandia reflects the growing influence of American popular culture and leisure architecture in the Caribbean during the mid-twentieth century. The cinema remained in use until its closure in 1983 and is now permanently closed.

The structure was built in reinforced concrete and is characterized by walls of glass bricks and rounded vertical concrete posts, elements that emphasize lightness, transparency, and streamlined form. Its architectural language clearly references Miami Art Deco, translating this internationally circulating style into a tropical, open-air typology adapted to Curaçao’s climate. Cinelandia thus exemplifies how global architectural and cultural models were locally appropriated and reinterpreted in the context of the island’s urban life.

Details

Location: Hendrikplein Z/N, Punda, Willemstad, Curaçao

Date: 1941

Architect: Pieter A. van Stuivenberg

Type: Cinema / open-air movie theatre

Status: Permanently closed (since 1983)

Source

AAA034, Caribbean Modernist Architecture

Mgr. Verriet Instituut

Salsbachweg 20, Willemstad, Curaçao — 1950–1952

The Mgr. Verriet Instituut was designed by Gerrit Rietveld and locally adapted and executed by Henk Nolte of the Curaçao Public Works Department. The complex was conceived as a combined home, school, and rehabilitation centre for children with disabilities, reflecting postwar ideals of social care and modernization in Curaçao. Since 2014, the building has no longer housed children and is currently used as a day-care facility.

The architecture is characterized by open gallery spaces, louvered walls and shutters that use wind as a natural cooling system, and large cantilevered roofs lined with reed mats for thermal insulation. The building also incorporates large gutters for rainwater collection. These features demonstrate how modernist architectural principles were translated into a tropical context, making the complex a clear example of mid-twentieth-century tropical architecture in Curaçao.

Details

Location: Salsbachweg 20, Willemstad, Curaçao

Date: 1950–1952

Architect: Gerrit Rietveld; local drawings and supervision by Henk Nolte (Curaçao Public Works Department)

Type: Institutional building (care, education, rehabilitation)

Current use: Day-care facility

Source

Modern Architecture of Curaçao, Michael A. Newton (DoCoMoMo Curaçao / LM Publishers, 2024)

https://1000awesomethingsaboutcuracao.com/2013/02/19/758-modernist-designer-rietveld-curacao/

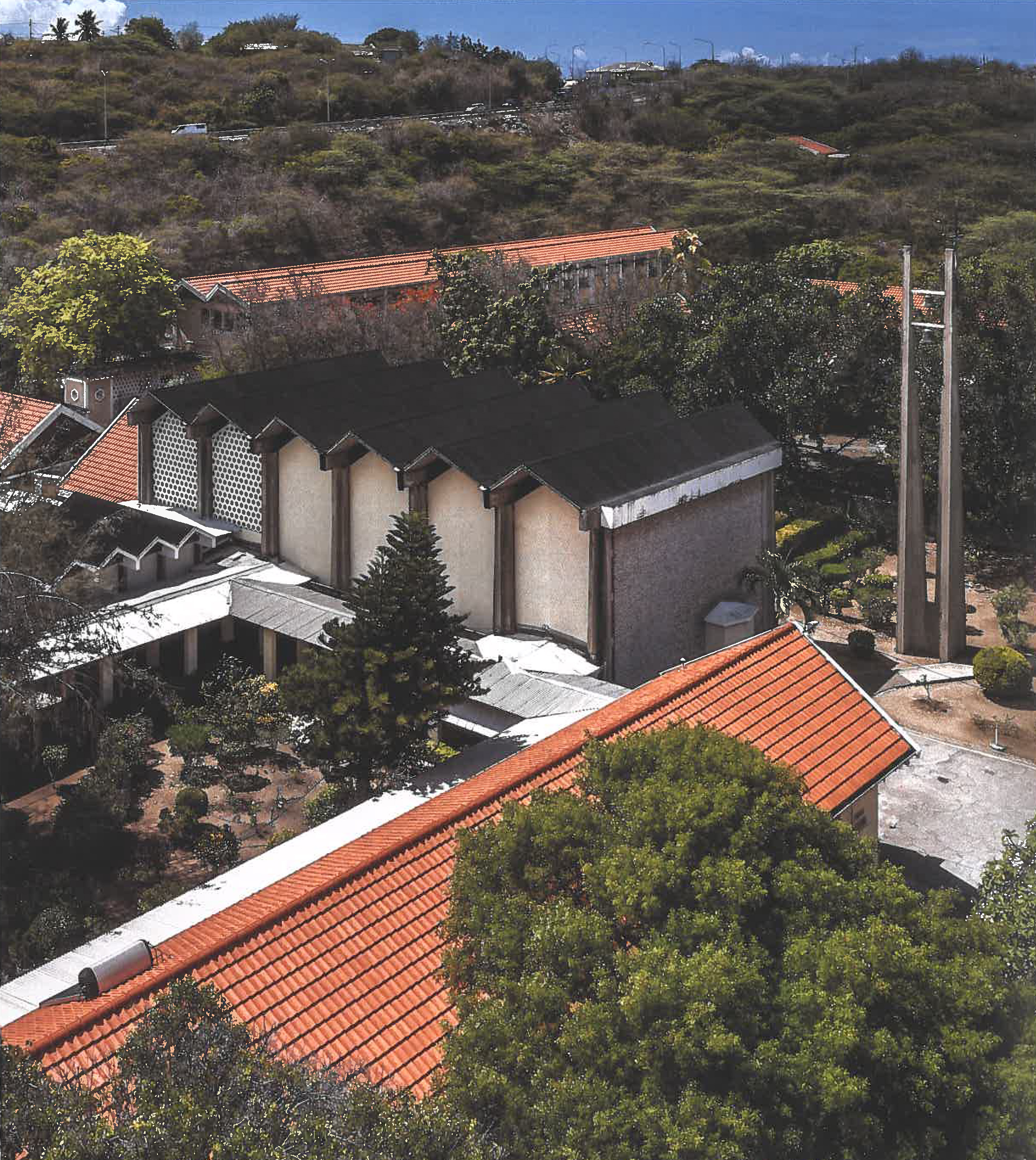

Kapel Klooster Alverna

Gouverneur van Lansbergeweg, Curaçao — 1957–1958

Kapel Klooster Alverna was designed by the Dutch architect Ben Smit, who moved to Curaçao in 1946 and established his own architectural practice on the island. The building was originally commissioned by the Congregation of the Franciscan Sisters of Mariadal from Roosendaal as a convent and boarding school. In the 1970s, the boarding school closed and the complex was converted into a retirement home for elderly care under the name Nos Lanterno.

The architecture is characterized by a zigzag-shaped roof, concrete columns, and the repeated use of hexagonal forms as a formal motif. The walls are covered with coral stone, and natural materials are used throughout the building. Combining expressive concrete forms with climatic and material adaptation, the complex stands as an example of Brutalist architecture and tropical modernism in mid-twentieth-century Curaçao.

Details

Location: Gouverneur van Lansbergeweg, Curaçao

Date: 1957–1958

Architect: Ben Smit

Type: Religious / institutional building

Current use: Elderly care facility (Nos Lanterno)

Source

Modern Architecture of Curaçao, Michael A. Newton (DoCoMoMo Curaçao / LM Publishers, 2024)

Vinck Residence

44 Kaya Seru Sablica, Sunset Heights, Curaçao — 2004–2006

The Vinck Residence was designed by Curaçao-based architect Ronny Lobo as a private home for his sister’s family, Sonia and Nelson Vinck-Lobo. The house is positioned on a hillside in Sunset Heights and commands a panoramic 180-degree view over the surrounding landscape. The colour scheme—composed of oranges, greens, yellows, and blues—was chosen by the clients, underscoring the personal and expressive character of the project within a contemporary residential context in Curaçao.

The building features a carport with a terrace constructed on top, curving walls with large overhangs, and expansive east-facing windows that emphasize light and views while providing shade. It is built using a combination of traditional and contemporary materials, including painted masonry blocks, aluminium and glass window frames, concrete floors, and a wooden roof structure with astatine shingles and plaster ceilings. The house exemplifies a twenty-first-century approach to architecture in Curaçao in which climate, landscape, and individual expression are brought together within a locally grounded construction tradition.

Details

Location: 44 Kaya Seru Sablica, Sunset Heights, Curaçao

Date: 2004–2006

Architect: Ronny Lobo

Structural engineer: John Antonius

Type: Private residence

Current use: Private dwelling

Source

https://curacaoartconsultancy.com/files/2023/11/WhatsApp-Image-2023-12-10-at-16.39.18-2.jpeg

https://curacaoartconsultancy.com/files/2023/11/WhatsApp-Image-2023-12-10-at-16.39.18-3.jpeg

Download PDF:

Get this article in print

21 January 2026

Share: Email, Instagram, WhatsApp