The Counter-White Cube: Embracing, Ever Touching Blackness

By Setareh Noorani

![Buro Stedelijk (2023). Design by Setareh Noorani and Jelmer Teunissen. Photo: Tom Philip Janssen.]()

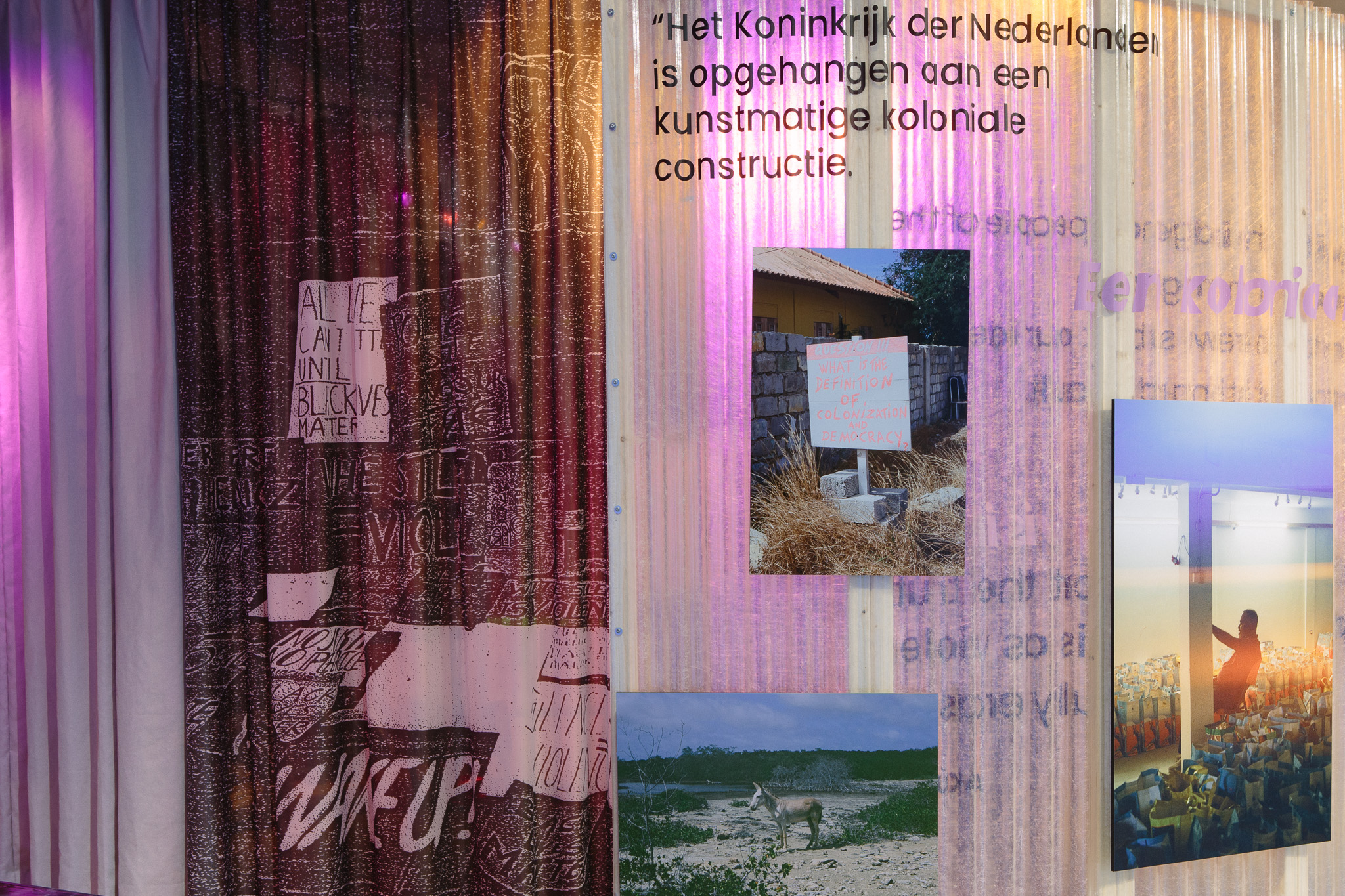

Buro Stedelijk (2023). Design by Setareh Noorani and Jelmer Teunissen. Photo: Tom Philip Janssen.

Art and architecture museums worldwide have adopted the white-cube as a means to situate and communicate the aesthetics of these practices. However, the universality of these spaces contrasts sharply with the cultural, social, political, and economic specificity needed to experience art and architecture as a true part of the lives, or ‘life’, from which they draw their raison d'être. As early as the 1970s, artists and designers have critiqued the white cube as an assemblage of constructs, where context, time, and space are controlled substances, to which audiences are introduced in carefully measured doses at the will of the museum. These museums are gatekeeping institutions, progressing the white cube experience in a loop of neoliberal cultural consumption: marketed rehearsals of sociality, and art speculation masked as individualised cultural experiences. And, as with every institution concerned with its own lifespan and relevancy, it must absorb the next societal concern. Within its sanitised white walls, it converts this concern into a mirage, devoid of its urgency and, therefore, its proximity to life.

![]() Zwart Manifest, The Black Archives, OSCAM. Exhibition design and scenography of art works by Setareh Noorani and Jelmer Teunissen. Photo: Zoë Zandwijken

Zwart Manifest, The Black Archives, OSCAM. Exhibition design and scenography of art works by Setareh Noorani and Jelmer Teunissen. Photo: Zoë Zandwijken

Art and architecture museums worldwide have adopted the white-cube as a means to situate and communicate the aesthetics of these practices. However, the universality of these spaces contrasts sharply with the cultural, social, political, and economic specificity needed to experience art and architecture as a true part of the lives, or ‘life’, from which they draw their raison d'être. As early as the 1970s, artists and designers have critiqued the white cube as an assemblage of constructs, where context, time, and space are controlled substances, to which audiences are introduced in carefully measured doses at the will of the museum. These museums are gatekeeping institutions, progressing the white cube experience in a loop of neoliberal cultural consumption: marketed rehearsals of sociality, and art speculation masked as individualised cultural experiences. And, as with every institution concerned with its own lifespan and relevancy, it must absorb the next societal concern. Within its sanitised white walls, it converts this concern into a mirage, devoid of its urgency and, therefore, its proximity to life.

In recent years, catalyzed by the George Floyd protests of 2020, Black and PoC (People of Color) representations are increasingly centered in museum spaces, for instance through embedding DEI-policies.These actions cater to a considerably large audience and body of cultural workers that had been previously left unattended. Museum directors were compelled to take a public stand on these matters ('kleur bekennen'): the museum space had explicitly become political, even fashionably so, serving as another possible platform for the people. Now, almost five years later, the uneasy feeling of a backtracking on these progressive politics is palpable. The accusation that museums are ‘woke’ originated in fringe right opinion, but this sentiment has become mainstream amid the current hostile political climate. Because most of these institutions rely on public funding, they are now vulnerable to cuts, especially as international priorities shift and national narratives lean toward conservatism, or worse, fascism. So, museums try to have it both ways: lean into the white cube, as a disciplining environment, a refuge from the complex contexts of life outside of the museum, and to attempt seducing a diverse audience to spend their time, energy, and money inside these walls. Can we ever come to approximate Blackness in museum spaces, if these institutions do not dare let go of the white cube? The verb ‘approximation’ is used intentionally here, as it does not consent to absorption, co-optation, or touch that negates the self and other, as Karen Barad reminds us that in touching there is a gap/void to reckon with that contains all possible other identities, and it can only be achieved by radically opening up oneself. Or to become ‘entangled with’, as Fred Moten invokes Denise Ferreira da Silva, a condition that is “difference without separation”. And so too ‘Blackness’ here is meant as a series of actions and rituals, fugitive at best, blurring what the institution intends to separate and enforce in neat aesthetic categories within a white cube; Blackness as entangled with whiteness by way of resistance.

This essay proposes that practicing ‘Blackness’, spatially and aesthetically, allows architects, designers, artists, and museum and cultural workers to ally differently and generously, with life and along life-affirming topics. This allyship must go beyond the façade representation of Black and PoC viewership, which easily can be absorbed by the white cube. These are representations where stereotypical Black forms of spatial gathering (like the stoop, porch, hair salons, and dance festivals) are co-opted to merely appear ‘in step with The Culture.’ This risks flattening the complex, layered experiences of a diverse, typically Othered, diasporic audience into one that is merely 'understood' and 'spoken to' via the devices of Hip Hop Culture and Afro-American life. The core question is: How might museums relate differently to Blackness, not as a consumable trend, but as something carrying the real political implication of solidarity with generative difference? As an author based in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and brought up in the distinct subtleties of a Dutch Black experience, I must consider the limitations of a universal Black experience, especially one solely tied to a Transatlantic history. Moreover, this essay draws upon my work as an architect and museum curator to make a definitive claim: we, Black and PoC spatial practitioners and cultural workers, do not need the white cube. To test this position, I engage with Tura Cousins Wilson, Principal Architect of SOCA in Toronto, Canada, whose work is situated on the intersection of art and architecture. Our discussion centers on his experiences challenging this framework and his reflections on Blackness. I also reflect on my experiences with Buro Stedelijk and Metro54, two Dutch-based arts spaces that actively engage the ‘otherwise’. From these, I list strategies that are 'counter' to the white cube and that aim to contaminate the programming and design of these museum spaces. This contamination is achieved by practicing Blackness, not only through visual or spatial interventions (though even shifting form can provoke resistance from practitioners in white cube contexts), but by questioning economies of solidarity, care, display, authorship, and participation. Who builds, sustains, and redefines the white cube, in step with the institution? And can we imagine otherwise, by offering tools and spaces as a way of prefigurative politics?

The White Cube Does Not Serve Us

The white cube stands in obvious tension with our times, where art and architecture are deeply shaped by politics, in aesthetics, conceptualisation, and social impact. The white cube offers museums non-offensive, non-political (neutral) environments. Environments where Big Art is platformed in its own bubble, divorced from grassroots realities. Yet, at their core, museums are grounded on certain representations, ideas and ideals of modernity and enlightenment-thinking; extractive ideologies still affecting humans and non-human life alike, which makes the white cube not neutral at all. At its core, the white cube upholds whiteness: it symbolically and materially enforces dominant norms, institutionalises white superiority, and renders ‘bodies out of place’. The white cube serves to legitimize the oppression of artists, architects, and cultural workers belonging to a precariat by coercing those who engage with it, through design or display or their work, to tune out the “infrastructure and imbalances” of the museum, and society at large. We live in a society where marginalized lives are continuously put on display for a voyeuristic audience, even as these lives grapple with the daily violence of a white system. Museums attempt to orient themselves toward Black contexts to remain relevant, or as Harry J. Elam jr. writes: “it remains exceedingly attractive and possible in this post-Black, postsoul age of Black cultural traffic to love Black cool and not love Black people.” The question remains: Is Blackness ever sincerely let into their spaces? Given this dynamic, the museum structure does not serve us. How do we disinvest from it? And how do we move, collectively, towards freedom? Like all institutions, museums reflect the narratives, programs, and representations society desires of them; this desire, therefore, must be fundamentally reimagined. Here, I invoke Katherine McKittrick, as she lays out that for this reimagination the extent of Black thought worlds are needed to breach the “heavy weight of dispossession and loss because these narratives (songs, poems, conversations, theories, debates, memories, arts, prompts, curiosities) are embedded with all sorts of liberatory clues and resistances.”

These Black worlds are transdisciplinary and translocal by definition, as aesthetic affinities have travelled along the Black Atlantic and Afrasian Sea (Indian Ocean) creating new “centres and margins, inclusions and exclusions; [...] new orientations, relationships, and alignments.” These mergers create new paths for solidarity, even when transposed to the Metropolitan by way of diaspora. They are rhizomatic in nature - boundlessly Black, instead of merely in opposition to the West. They are paths that “[challenge and discard] the universal”, instead believing in opacity as strategy; this is exactly where Blackness becomes incompatible with the transparency and obviousness of the world as told by the white cube. And, importantly, Blackness here can liberate broadly, as it inserts the political implications of radical love, difference, and solidarity and ties it concretely to geographies and spaces for liberation.

Building Anew

The white cube must be dismantled. In its place a space for conviviality must be built anew.

This proposition is, of course, informed by Audre Lorde's famous essay, "The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle The Master’s House." Specifically, I am thinking through her statement that we need interdependence and difference that nurtures community. This stands in sharp opposition to the white cube, which represents the extractive and colonial value system of Western institutions that seeks both to pigeonhole identities and extract surplus value from them. Difference is the integral hinge that moves us away from solely thinking about the identity-self, as Katherine McKittrick suggests, and toward thinking of Blackness as a strategy or mode to ensure freedom remains a horizon: rooted in struggle for human and non-human, our lives and the ecologies that surround us. The contemporary cultural landscape offers few spaces that successfully practice this Blackness. Spaces that acknowledge errantry consistent with people’s “will to identity”, or “freedom within particular surroundings”, without falling into the trappings of the “identity-self”, which excludes kinmaking beyond our lives and bodies.

In the Netherlands, Metro54 and Buro Stedelijk serve as key examples: two spaces that have built their physical presence in unexpected environments, rhizoming out from their primary locations through temporary interventions amidst the diverse communities they specifically seek to engage. Metro54, for instance, landed at the Westerdok in Amsterdam after years of programming and curating cutting-edge art, sound, and discursive practices throughout the city. The team, represented by Amal Alhaag and Nadine Stijns, curated 'A Funeral For Street Culture' at Framer Framed (2021). This exhibition directly interrogated the position of street culture and the Black experience when Black and PoC bodies are disallowed ownership over these exact streets. The question, “What do we do when the hype dies?” is a prescient one in the light of this essay’s argument. I consider its exhibition design to be one of my more successful collaborations, precisely because of the challenge posed by Amal Alhaag and Nadine Stijns to address the overlap and interrelation of different practices of Blackness. To find refuge in the presentation space of Framer Framed was to turn away from the white cube and understand the space as a holding space for our fragmented, intersecting, errant bodies. Its accompanying design statement articulated this approach: “We locate erasures, enclosures, and vantage points in order to reflect on what we are putting on a pedestal. What are we offering a stage and therefore: what institution are we staging?”

A Funeral for Street Culture (2021), Metro54, Framer Framed. Exhibition design and scenography of art works by Setareh Noorani and Jelmer Teunissen. Photo: Eva Broekema

Pris Roos, ‘'I See I See I See I See Daily Paper, Clan de Banlieue, Sumibu and Concrete Blossom in Rotterdam-West' (2021)’, A Funeral for Street Culture, Metro54, Framer Framed. Exhibition design and scenography of art works by Setareh Noorani and Jelmer Teunissen. Photo: Eva Broekema

Buro Stedelijk, in contrast, is nurtured within the confines of the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam by a no less dedicated and tight-knit team, including its co-founding curator, project manager, and producers, all indicated as ‘collaborators’ on par with the invited artists and designers. In the first three years with co-founding curator Rita Ouédraogo, Buro Stedelijk extended this horizontality into an ongoing offering of ‘manifestations,’ including talks, design interventions, artworks, and ongoing artist studios. Here again, I was fortunate to design Buro Stedelijk’s first spatial appearance, with my collaborator Jelmer Teunissen. The brief provided an opportunity to rethink what might be needed to rehearse an institution otherwise. What infrastructures are harnessed to enact the porosity needed to dream collective worlds, to hold freedom for each other? Ultimately, Metro54 and Buro Stedelijk are both spaces where practicing conviviality and interdependence inform their programming. Collaborators and internal teams actively work to counter the hierarchy of values attached to titles and visibility, a hierarchy so inherent to the traditional art and architecture world.

Buro Stedelijk (2023). Design by Setareh Noorani and Jelmer Teunissen. Photo: Tom Philip Janssen.

Buro Stedelijk (2023). Design by Setareh Noorani and Jelmer Teunissen. Photo: Tom Philip Janssen.

To reflect upon Blackness practiced outside of the Netherlands, I spoke with Tura Cousins Wilson in Toronto, Canada. He is the principal of the Studio of Contemporary Architecture (SOCA), a practice operating between art and architecture that collaborates with artists like Theaster Gates and Magdalene Odundo. I selected this context because, despite its own colonial history, the city and country possess a Black and PoC demographic not entirely dissimilar from that of the Netherlands. Interestingly, this specific Black and PoC experience is marginalized not only by its position on the edges of the United States but also by grappling with a cultural consciousness built on values of 'tolerance'. This 'tolerance,' much like in the Netherlands, effectively renders the complaints of marginalized persons invisible.

Tura Cousins Wilson relays that SOCA's work questions the process and value of institutionalizing, finding merit instead in smaller organizations and their ability to stay nimble. He sees an opportunity for architects to “push beyond the brief” and engage their expertise to welcome additional voices to consult, interact, and make alongside them, thinking about “who can add value to the ongoing conversation.” Cousins Wilson concluded that the white cube “might not be the best venue for [this type of] conversation or engagement.” Institutions at large, he argues, need to consider their position and ability to truly redistribute resources, help build capacity, and move beyond their comfort zones by moving into the locality where the communities they want to engage are found through programming. Cousins Wilson stresses that “Blackness should be the starting point for a much broader conversation [...] and museums need to be thinking about Blackness and that comes with genuine interest and curiosity, as opposed to only hiring and acquiring work.” The multilayeredness of Blackness, he suggests, can bring perspectives relegated to the margins into a broader conversation on stories of life, urbanity, and more.

Magdalene Odundo: A Dialogue with Objects at the Gardiner Museum in Toronto - SOCA designed exhibition. The design transforms the white cube space into a 'clay cube' treating the walls with textured limewash paint and creating broken circular plinths covered in dark plaster which pick up on the metallic quality of Odundo's vessels; Photo by Jack McCombe

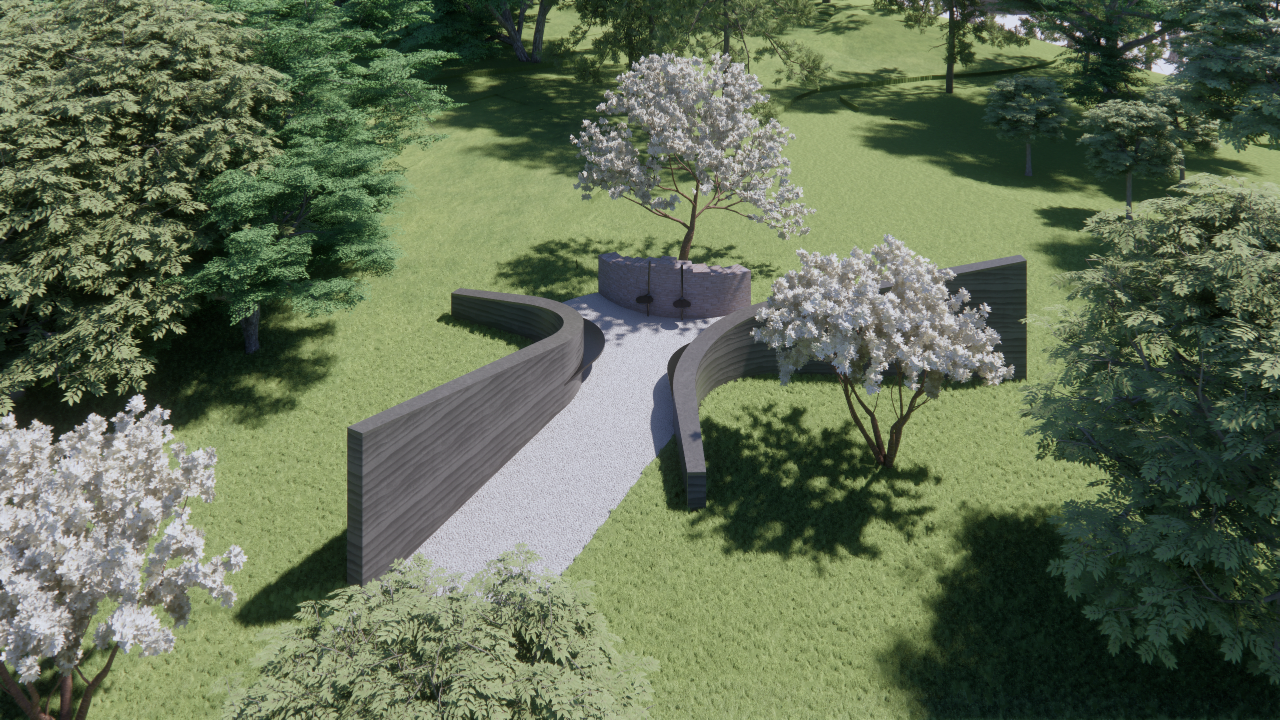

Samuel Adams Memorial, Oakville, Ontario, Canada - SOCA designed a memorial to Samuel Adams, an African American blacksmith who migrated to Canada in the 1850's via the Underground Railroad and settled in Oakville Ontario. The design uses salvaged foundation stones from the recently demolished Adams family home, anchoring the site with authentic material memory. These stones are framed by newly constructed rammed earth walls that evoke permanence and craft. Sculptural iron seating gestures to Adams’ blacksmithing trade and longer histories of African ironwork; Rendering by SOCA

The Counter-White Cube

SOCA, Metro54, and Buro Stedelijk share a common thread of strategies that are 'counter to' the white cube. These methods prioritize dismantling through active dialogue, undoing frameworks, and reframing relationality - always centering refusal. Their approaches assemble publics that disrupt, move queer, and counter established norms. They refuse to see Blackness as relegated to the margins or the counter-white cube as "separatist spaces," positioning both instead as viable and vital alternatives to traditional institutions of art, architecture, and design. Blackness here is not to be “trafficked” without consent, but a method always in reference to the “history and politics of Black, [marginalized] struggle”. By practicing Blackness, the architectures and infrastructures through which publics can organize and build anew contain instances of prefigurative politics.

The counter-white cube, as a spatial proposition, is in lockstep with a program that offers a radical rehearsal of solidarity, of togetherness in difference. It thus adheres to and actively promotes additional values, including: horizontality, communality, civic capacity (civicity), emancipation, autonomy, and opacity. To accomplish integrating these values, a radical porosity, a concept of ‘touching oneself, touching the other’, must be institutionalized. In the counter-white cube, the presence of community is marked as layers of accumulated activity, knowledge, and resources. Porosity, in turn, acts as the agent that allows these layers to leak back into the community. Infrastructure is that which is both questioned, practiced, and actively on display. Aesthetics makes a direct relation with politics. Fred Moten supports this notion of radical sociality. He invokes the Black Panther Bobby Lee, who sought to organize white working-class people into a collective demand and states that in contrast to the separations sought by whiteness, “Blackness blurs by cutting, in touch.”

1

Brian O’Doherty, Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space, The Lapis Press, 1986, http://www.loc.gov/catdir/bios/ucal052/99042724.html.; Setareh Noorani, ‘Rehearsing Institutional De-Scripting: A Machine for Manifestations,’ in How We Made Noise: Reimagining the Museum from Within, ed. Rita Ouédraogo. Onomatopee, Buro Stedelijk, 2025.

2 Nesrine Malik, “The Black Lives Matter Era Is Over. It Taught Us the Limits of Diversity for Diversity’s Sake,” The Guardian, October 17, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/article/2024/may/20/Black-lives-matter-diversity-racial-equality.

3 Leser, Julia, Alice Millar, Marlena Nikody, and Pia Schramm. 2025. “Right-Wing Populism and Museums: Findings from an Interview Study in the UK, Poland and Germany”. Museum & Society 23 (2):109-25. https://doi.org/10.29311/mas.v23i2.4526.

4 Karen Barad; On Touching—the Inhuman That Therefore I Am. differences 1 December 2012; 23 (3): 206–223. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/10407391-1892943

5

‘Notes’ in Fred Moten, Black and Blur, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822372226, 313.

6

Moten, Black and Blur.

7

Tura Cousins Wilson, interview by Setareh Noorani, December 2, 2025

8

Nirmal Puwar, ed. Space Invaders: Race, Gender and Bodies Out of Place. Angel Court: Bloomsbury Academic, 2004. Accessed November 30, 2025. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474215565.

9

Martin Herbert, “What the ‘White Cube’ Means Now,” ArtReview, January 21, 2021, https://artreview.com/what-the-white-cube-means-now/.

10

Harry Justin Elam, “Change Clothes and Go: A Postscript to PostBlackness,” in Black Cultural Traffic, Harry Justin Elam and Kennell Jackson, eds. University of Michigan Press eBooks, 2005, https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11883, 386.

11

John Duda, trans., “Gilles Deleuze, ‘Instincts and Institutions,’” InterActivist Info Exchange, 2003, accessed November 11, 2025, http://dev.autonomedia.org/node/2525.

12

Katherine McKittrick, “Curiosities (My Heart Makes My Head Swim).” Dear Science and Other Stories (Durham: Duke University Press, 2021), 7.

13

Claire Lubell and Rafico Ruiz, eds., Fugitive Archives: A Sourcebook for Centring Africa in Histories of Architecture (Jap Sam Books, Canadian Centre for Architecture, 2023).

14

Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing, University of Michigan Press eBooks, 1997, https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.10257.

15

Glissant, Poetics of Relation, 20.

16

Audre Lorde, The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House (Penguin Classics, 2018).

17

Glissant, Poetics of Relation, 20.; Annie Galvin, “Public Thinker: Katherine McKittrick on Black Methodologies and Other Ways of Being,” Public Books, April 12, 2023, https://www.publicbooks.org/public-thinker-katherine-mckittrick-on-Black-methodologies-and-other-ways-of-being/.

18

Framer Framed, “Project: A Funeral for Street Culture; Metro54,” October 7, 2021, https://framerframed.nl/en/exposities/expositie-a-funeral-for-street-culture/.

19

Setareh Noorani, “Metro54 @ Framer Framed – a Funeral for Street Culture (2021),” n.d., https://setarehnoorani.nl/project/metro54-framer-framed-a-funeral-for-street-culture-2021/.

20

Setareh Noorani, ‘Rehearsing Institutional De-Scripting: A Machine for Manifestations,’ in How We Made Noise: Reimagining the Museum from Within, ed. Rita Ouédraogo. Onomatopee, Buro Stedelijk, 2025.

21

Tura Cousins Wilson, interview by Setareh Noorani, December 2, 2025

22

Tura Cousins Wilson, interview by Setareh Noorani, December 2, 2025

23

Interview with Salome Asega, Emanuel Admassu, in Where Is Africa?, CARA

24

Harry Justin Elam, “Change Clothes and Go: A Postscript to PostBlackness,” in Black Cultural Traffic, Harry Justin Elam and Kennell Jackson, eds. University of Michigan Press eBooks, 2005, https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11883, 382.

2 Nesrine Malik, “The Black Lives Matter Era Is Over. It Taught Us the Limits of Diversity for Diversity’s Sake,” The Guardian, October 17, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/article/2024/may/20/Black-lives-matter-diversity-racial-equality.

3 Leser, Julia, Alice Millar, Marlena Nikody, and Pia Schramm. 2025. “Right-Wing Populism and Museums: Findings from an Interview Study in the UK, Poland and Germany”. Museum & Society 23 (2):109-25. https://doi.org/10.29311/mas.v23i2.4526.

4 Karen Barad; On Touching—the Inhuman That Therefore I Am. differences 1 December 2012; 23 (3): 206–223. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/10407391-1892943

5

‘Notes’ in Fred Moten, Black and Blur, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822372226, 313.

6

Moten, Black and Blur.

7

Tura Cousins Wilson, interview by Setareh Noorani, December 2, 2025

8

Nirmal Puwar, ed. Space Invaders: Race, Gender and Bodies Out of Place. Angel Court: Bloomsbury Academic, 2004. Accessed November 30, 2025. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474215565.

9

Martin Herbert, “What the ‘White Cube’ Means Now,” ArtReview, January 21, 2021, https://artreview.com/what-the-white-cube-means-now/.

10

Harry Justin Elam, “Change Clothes and Go: A Postscript to PostBlackness,” in Black Cultural Traffic, Harry Justin Elam and Kennell Jackson, eds. University of Michigan Press eBooks, 2005, https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11883, 386.

11

John Duda, trans., “Gilles Deleuze, ‘Instincts and Institutions,’” InterActivist Info Exchange, 2003, accessed November 11, 2025, http://dev.autonomedia.org/node/2525.

12

Katherine McKittrick, “Curiosities (My Heart Makes My Head Swim).” Dear Science and Other Stories (Durham: Duke University Press, 2021), 7.

13

Claire Lubell and Rafico Ruiz, eds., Fugitive Archives: A Sourcebook for Centring Africa in Histories of Architecture (Jap Sam Books, Canadian Centre for Architecture, 2023).

14

Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing, University of Michigan Press eBooks, 1997, https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.10257.

15

Glissant, Poetics of Relation, 20.

16

Audre Lorde, The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House (Penguin Classics, 2018).

17

Glissant, Poetics of Relation, 20.; Annie Galvin, “Public Thinker: Katherine McKittrick on Black Methodologies and Other Ways of Being,” Public Books, April 12, 2023, https://www.publicbooks.org/public-thinker-katherine-mckittrick-on-Black-methodologies-and-other-ways-of-being/.

18

Framer Framed, “Project: A Funeral for Street Culture; Metro54,” October 7, 2021, https://framerframed.nl/en/exposities/expositie-a-funeral-for-street-culture/.

19

Setareh Noorani, “Metro54 @ Framer Framed – a Funeral for Street Culture (2021),” n.d., https://setarehnoorani.nl/project/metro54-framer-framed-a-funeral-for-street-culture-2021/.

20

Setareh Noorani, ‘Rehearsing Institutional De-Scripting: A Machine for Manifestations,’ in How We Made Noise: Reimagining the Museum from Within, ed. Rita Ouédraogo. Onomatopee, Buro Stedelijk, 2025.

21

Tura Cousins Wilson, interview by Setareh Noorani, December 2, 2025

22

Tura Cousins Wilson, interview by Setareh Noorani, December 2, 2025

23

Interview with Salome Asega, Emanuel Admassu, in Where Is Africa?, CARA

24

Harry Justin Elam, “Change Clothes and Go: A Postscript to PostBlackness,” in Black Cultural Traffic, Harry Justin Elam and Kennell Jackson, eds. University of Michigan Press eBooks, 2005, https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11883, 382.

Images courtesy of Setareh Noorani

Download PDF:

Get this article in print

21 January 2026

Share: Email, Instagram, WhatsApp