The Domino Effect

By Christian Cassiel & Andu Masebo

A conversation between Christian Cassiel and Andu Masebo about gifts, time, and the spaces objects move through.

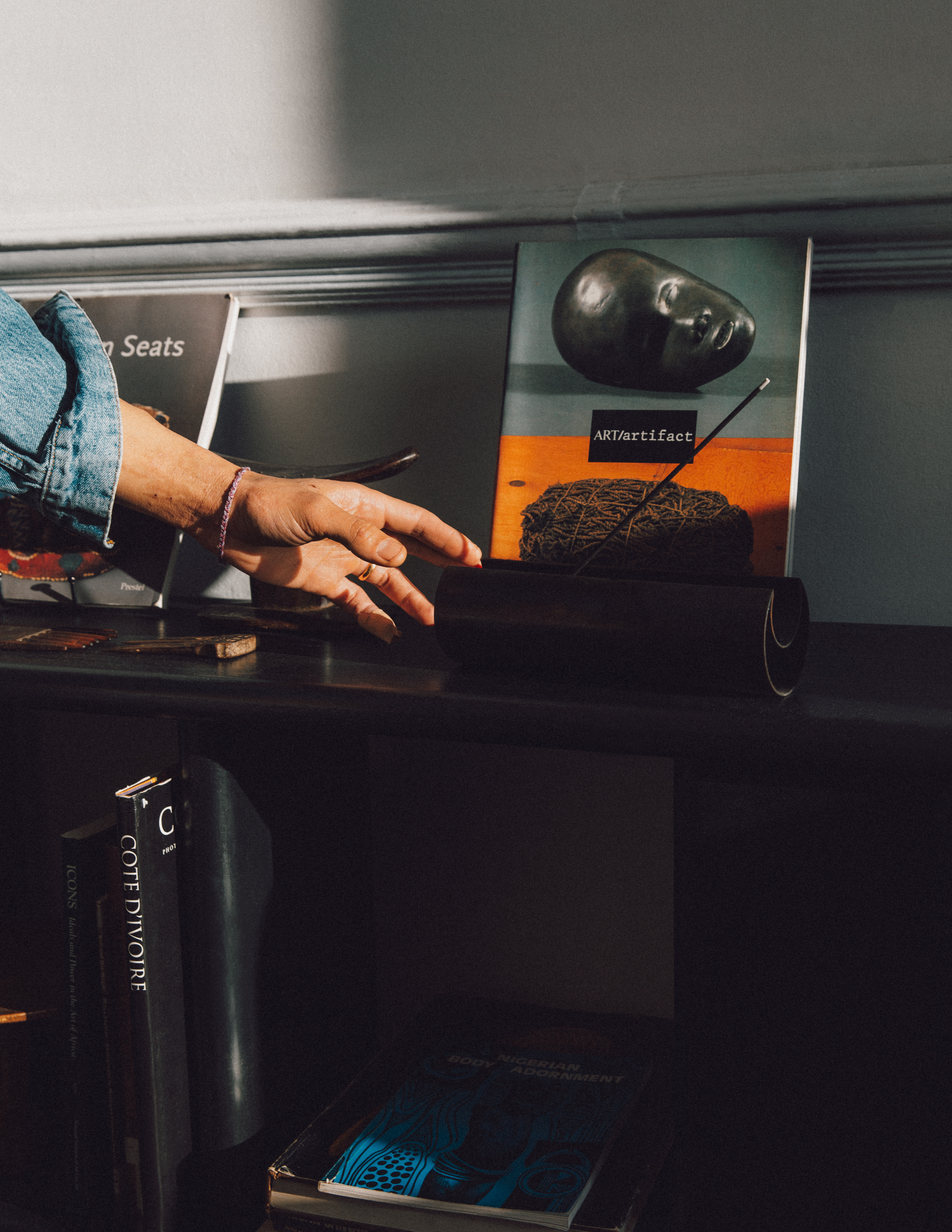

![Furniture by Andu Masebo, Library by Seed Archives for Making Room.]()

Furniture by Andu Masebo, Library by Seed Archives for Making Room.

Christian Cassiel:

I’ve known about your practice for a long time, even way before Making Room. I followed you as you were one of the designers that I admired. But through running Seed, many of those people have now become friends and collaborators. That’s really cool to me.

Andu Masebo:

I actually knew about Seed Archives before we met. What drew me in was the similar energy. We were both really excited about the possibility of sharing and creating a space that encourages interaction. Making Room was about that: giving people the freedom to make, learn, and explore their environment in new ways.

CC:

It felt generous from the start. Not just giving space, but giving people the chance to make their own gifts. Objects moving through different hands, gaining meaning as they travel.

Furniture by Andu Masebo, Library by Seed Archives for Making Room.

AM:

That’s the domino effect. Small acts accumulate. People tell me years later that something they experienced at Making Room shaped what they’re doing today. Everyone contributed freely, time, knowledge, ideas. There was no transactional expectation, which changed the energy entirely. And sometimes the act of giving, as opposed to selling, is one of those levers you can pull. You don’t have to sell everything that you give.

CC:

Exactly. I believe doing things openly, without a specific agenda, lets things unfold abundantly. Even for me, that first day of Making Room, someone brought a complete set of rare New Culture magazines from 1978. A friend had just told me about them a week prior, and I was trying to get them for Seed but couldn’t afford them. This person ended up just giving them to me. Sometimes things make a return in the most unexpected ways.

CC:

Speaking of gifts, the incense holder you gave me. What inspired it?

AM:

I want to be able to explore lots of things at once, but I also wanted to experiment without spending a year’s salary. I was thinking about movement in relation to burning incense. Incense burners hold something that disperses fragrance throughout a room, but what if there was a way to articulate that movement?

I created a series of objects that spun, swung, or rocked, but most ended up expensive to produce. So I simplified it. Two metal tubes inside each other that rock back and forth, easy to make in my workshop. It’s about resourcefulness, balancing size, negative space, and materials to make something accessible yet effective. Mild steel, heat-treated with wax, it holds something that burns without the surface melting or rusting. The final form emerges through that careful process.

I created a series of objects that spun, swung, or rocked, but most ended up expensive to produce. So I simplified it. Two metal tubes inside each other that rock back and forth, easy to make in my workshop. It’s about resourcefulness, balancing size, negative space, and materials to make something accessible yet effective. Mild steel, heat-treated with wax, it holds something that burns without the surface melting or rusting. The final form emerges through that careful process.

CC:

When we were burning incense in them, I remember saying, “These are going to sell fast,” and you replied, “No, I’ll give them away.” What led you to that decision?

AM:

I’d say, scale and time. The size means you can give it to someone without becoming a burden. You know, if you give someone a chair, they need a place in their home for that chair to exist. Also the price point, how much time it takes to make. You can’t just give a day away freely, a day of your life on this earth. But you could give an hour away to most people, out of a sense of compassion.

The shelf that’s now in Seed took about a week. Although it was made for another reason, it existed beyond that moment. Giving it to you came from thinking about where it could live, and the most beautiful place I thought it could exist was in your context, in your space, around your things.

The shelf that’s now in Seed took about a week. Although it was made for another reason, it existed beyond that moment. Giving it to you came from thinking about where it could live, and the most beautiful place I thought it could exist was in your context, in your space, around your things.

AM:

To me, the beauty of Seed, and of growing up in London, which is so rich in its makeup and mix, is that there’s not an immediate requirement to define yourself. You’re surrounded by influences that circulate through the city, and even without direct ties, certain cultures can feel familiar because they’re part of its fabric. When it comes to making work, you’re always drawing from lots of things, even while still trying to understand how they sit together. Spaces like Seed are useful for going down that road, without needing to fix anything in place.

CC:

What I really love about your practice is that you feel like a designer in the truest sense. You don’t seem pressured to produce certain forms. You’re playful, experimental, and attentive to everyday observation. There’s so much around us to draw from. And I think sometimes, especially around culture and heritage, there’s a pressure to construct a certain narrative, to make the work seem legible, fundable, or easier to write about.

AM:

Ten years ago, the only way I could have been understood as a successful designer was through my heritage. From a white gaze, that was the only space available. Your skin is brown, tell us where you’re from. That was how my work could be legible.

Something has shifted in the last five to ten years. I’m in awe of peers who deeply interrogate and express their heritage through their work. I’m equally in awe of people whose work is more emotionally detached, focused on form, function, or feeling. I think what I’m grateful for is the ability to move between those positions. I can explore heritage if I want to, but it’s not imposed. I can still make work that connects with people without having to fit into a predefined box.

Something has shifted in the last five to ten years. I’m in awe of peers who deeply interrogate and express their heritage through their work. I’m equally in awe of people whose work is more emotionally detached, focused on form, function, or feeling. I think what I’m grateful for is the ability to move between those positions. I can explore heritage if I want to, but it’s not imposed. I can still make work that connects with people without having to fit into a predefined box.

AM:

Man, do you know what I would love in exchange for this gift? At some point, a series of moments around the shelf. If you could send me those pictures. That would be a beautiful way for me to feel that it’s been lived with.

CC:

A hundred percent. Documentation is central to how I work. People often think Seed is the archive, the books and the objects, but I’m a photographer. My way of archiving is documenting people experiencing the space. It’s almost like a set I’ve created, where I capture the intimate relationship people have with it.

I think that’s part of why Seed has become known. People see friends, peers, people they recognise experiencing the space, and it makes them want to be there too. Seed is open to everyone, but it was made for our community first and foremost. People need to see themselves in a space to feel like it’s for them.

People come back because they know what to expect. They come alone, meet someone, and return together. It becomes a kind of collaborative research.

I think that’s part of why Seed has become known. People see friends, peers, people they recognise experiencing the space, and it makes them want to be there too. Seed is open to everyone, but it was made for our community first and foremost. People need to see themselves in a space to feel like it’s for them.

People come back because they know what to expect. They come alone, meet someone, and return together. It becomes a kind of collaborative research.

AM:

Yeah. That’s the domino right there. That’s the domino effect.

Credits:

Photography: Christian Cassiel

Concept & editing: Keesje Heldoorn

Download PDF:

Get this article in print

21 January 2026

Share: Email, Instagram, WhatsApp