When the Shops Close: Informal Spaces and Social Belonging on a Gentrifying Street

By Elisa Heath & Nora Marica

![]()

Two years ago, we began roaming the streets of our own neighbourhood with new eyes. As part of the IN-FORM-ALL project, which highlights counterpublics between Rotterdam and Johannesburg, we set out to observe informal social spaces embedded in everyday city life. Our focus turned to the Nieuwe Binnenweg, one of the busiest and most rapidly gentrifying streets in Rotterdam West.

![]()

Two years ago, we began roaming the streets of our own neighbourhood with new eyes. As part of the IN-FORM-ALL project, which highlights counterpublics between Rotterdam and Johannesburg, we set out to observe informal social spaces embedded in everyday city life. Our focus turned to the Nieuwe Binnenweg, one of the busiest and most rapidly gentrifying streets in Rotterdam West.

Gentrification along the Nieuwe Binnenweg is reshaping both the street’s aesthetics and its social fabric. Trendy establishments with curated facades and polished interiors increasingly erode the long-standing places that have defined the character of the street. During the day, these informal spaces are often overshadowed. At night, however, when cafés and shops close, their presence becomes visible, revealing their importance to livability, safety, and social cohesion.

Once known as a rougher part of the city, Rotterdam West has in recent years been rebranded as ‘trendy’ and ‘up-and-coming’. While this transformation introduces new amenities such as cafés, boutiques, and lunchrooms, it also carries consequences. Gentrification does not simply add to the urban landscape; it displaces, marginalises, or renders invisible existing communities and the spaces that serve them. The dominance of daytime-oriented, commercial venues diminishes the visibility and perceived value of long-standing community spaces. These spaces come to the foreground at night, when they are the ones that remain.

Our visual research documents how gentrification manifests through a distinct visual language. Many new cafés, bars, and shops along the Nieuwe Binnenweg differ from long-standing businesses that have given the street its warm and lively character. Their facades are often white, with black minimalist typography, and their interiors are dominated by wood or stainless steel. This formula, now widespread across the Netherlands, is mostly aimed at young urban professionals. In contrast, businesses such as a Nigerian restaurant and a Syrian supermarket are marked by bold colours, layered signage, and eclectic interiors.

The coexistence of these places reveals a dichotomy that goes beyond questions of taste. In his book Chromophobia, David Batchelor describes a long-standing Western fear of colour, noting how, since Antiquity, colour has been systematically marginalised, reviled, and degraded. The use of colour has long carried associations of excess, of being “too much”, or of being linked to the “foreign” or the “other”. White, by contrast, has been consistently associated with what is modern, rational, clean, and controlled. Within this context, the dominance of white in buildings and interiors echoes these hierarchies. A clear example of this is the white cube: what was once proposed as a neutral or equalising space ultimately resulted in the exclusion of non-Western aesthetics and traditions.

In Rotterdam West, many of the colourful, open-late establishments are run by people with non-Western backgrounds, who themselves or whose families migrated to Rotterdam. When the city “improves” the area with gentrified spaces that echo this chromophobic aesthetic, these places are overshadowed, despite the crucial role they play in fostering community, belonging, and informal care networks.

Jane Jacobs’ concept of ‘eyes on the street’ offers a useful lens here. In The Death and Life of Great American Cities, she argues that safety in public space emerges from constant presence and informal social control. During the day, the Nieuwe Binnenweg feels animated and relatively secure. Yet when night falls and many trendy venues close, the true social backbone of the street becomes visible.

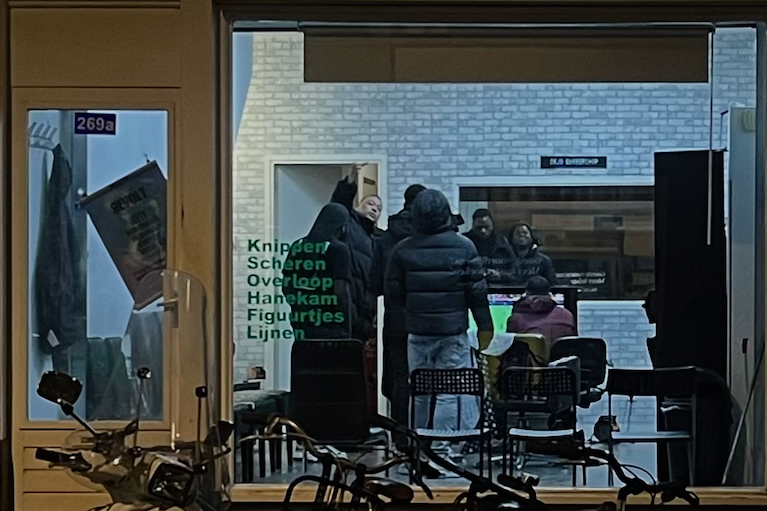

While the gentrified shops leave behind empty streets, long-standing informal spaces remain active: an Afro barbershop where friends gather to watch football, a night shop still open late, and a shoarma restaurant still serving customers well past regular hours. Their continued presence keeps the street alive, offering safety, familiarity, and a sense of belonging. These places function as the street’s true guardians.

The case of the Nieuwe Binnenweg demonstrates that urban renewal involves more than just physical or economic change. It also entails shifting values, aesthetics, and forms of social cohesion. As trendy cafés, restaurants, and shops dominate the streetscape during the day and contribute to a particular Western urban aesthetic, the diverse and colourful places that are essential for community building and social safety fade into the background. Their value becomes evident only at night, when these community-based places remain as sites of encounter, social control, and belonging.

These contrasts reveal that behind the seemingly neutral narrative of improvement lies a system that marginalises not only certain aesthetics, but also the communities and traditions attached to them. It is precisely these informal, often overlooked places that sustain urban life. When the shops close and the street grows quiet, the true spirit of the street, informal, colourful, and communal, emerges and endures.

Credits:

Images courtesy of Elisa Heath & Nora Marica

Download PDF:

Get this article in print

21 January 2026

Share: Email, Instagram, WhatsApp